Copyright 2015 © Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. All Rights Reserved. . Powered by Pelrox Technologies Ltd

ISSN 03 02 4660 AN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA

Quick Navigation

Niger J Paediatr 2016; 43 (4): 252 – 257

ORIGINAL

Onubogu UC

Implementation of Kangaroo

Okoh BA

mother care by health workers in

Nigeria

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i4.4

Accepted: 4th August 2016

Abstract :

Background: Kangaroo

122(77.7%)

doctors

and

35

Mother Care (KMC) has been

(22.3%) nurses were studied. 84

Onubogu UC (

)

proven to significantly improve

(53.5%) practiced KMC. The rea-

Department of Paediatrics,

growth, reduce mortality and mor-

sons for not practicing KMC were

Braithwaite Memorial Specialist

Hospital, Port Harcourt, Rivers State.

bidity in low birth weight infants.

lack of policy reported by 43

Nigeria

The impact of KMC in newborn

(58.9%) and inadequate place for

Email: utchayonubogu@yahoo.co.uk

care is expected to be greatest in

the mothers to stay 30(41%).The

Africa due to limitations in health

level of practice was significantly

Okoh BA

care.

higher among respondents that

Department of Paediatrics,

Objective: The

aim of

this study

worked in facilities that care for

University of Port Harcourt Teaching

was to determine the proportion

sick neonates (p = 0.049), have

Hospital, Port Harcourt. Rivers State,

of

Nigerian health workers ren-

functional incubators (p = 0.014)

Nigeria

dering paediatric care who prac-

and practice KMC (p < 0.001).

tice KMC in their institution, and

Conclusion: Hospitals

should have

identify some challenges affecting

a

written KMC policy and provide

the practice of KMC in Nigerian

KMC wards in order to improve

health institutions.

implementation of KMC practice

Method: A

cross sectional

study

in

Nigeria.

of

the participants at 45 annual

th

scientific conference of the Paedi-

Keywords: Health

workers,

atric Association of Nigeria was

kangaroo mother care, low birth

conducted.

weight, neonate, Nigeria

Result: A

total of157

respondents

Introduction

located often in distant referral hospitals which are un-

derstaffed and ill-equipped. The implementation of

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) is the early, prolonged

KMC on an appreciable scale in the relatively few health

and

continuous skin – to – skin contact between the

facilities in low income countries is the only way this

mother (or substitute) and her low birth weight infant,

strategy can make significant impact in reducing the

both in hospital and after early discharge, until at least

unacceptably high neonatal mortality in these low in-

the 40th week of postnatal gestation age. The develop-

1

come countries.

ment of this method of care in early 1970s, was moti-

vated by problems arising from shortage of incubators,

In

Nigeria, it was estimated that KMC would save over

overcrowding and the impact of mother and newborn

19,000 lives by 2015 if all preterm neonates were to be

reached. For this to succeed, the health worker that ren-

5

separation in hospitals caring for low birth weight in-

fants.

1

ders pediatric care would have to start implementing

KMC in the health facility where they practice and then

KMC has been proven to significantly improve growth,

aim to scale it up to involve the grass roots. According

reduce mortality and morbidity particularly from hypo-

to

reports by Victora et al, one of the reasons attributed

thermia, hypoglycemia and nosocomial sepsis in neo-

to

poor expansion of KMC practice on a large scale in

nates with birth weight of <2000g. Lawn et al, in a

2,3

most low- and middle-income countries is because in

meta-analysis of three randomized control trial studies

these countries, KMC implementation started at a teach-

reported that KMC decreased mortality in neonates with

ing or other tertiary hospital without expanding to dis-

trict hospitals. Within the health facility, Provision of a

6

birth weight of <2000 g by 51%. More than three dec-

4

ades after its development, KMC is now recognized by

private comfortable environment and having written

global experts as an integral part of essential newborn

protocols has also been identified as one of the support-

ing factors that promote KMC practice.

6,7

care.

In

Nigeria

It

is expected that the impact of KMC in newborn care

KMC was first introduced in the late 1990s through a

would be greatest in Africa with a significant number of

resident pediatrician at the University of Lagos Teaching

low income countries. This is because of limited options

Hospital following a month-long training in Bogotá,

Colombia. KMC was also declared as the best option of

8

for care for preterm babies with few neonatal care units,

253

practice in 1998 during the 29 annual general and sci-

th

Respondents scoring less than 50% were considered to

entific conference of the paediatric association of Nige-

have

poor practice, those scoring 50 – 75% moderate,

ria.

More than 2 decades after the adoption of KMC in

[9]

and

those scoring above 75% as having good practice of

Nigeria, with various training programs organized by

KMC.

ministry of health and Non-governmental organizations

Data collected was entered and analyzed using EPI

at

different levels of heath care from tertiary to primary,

INFO version 7. Chi- squared test and Fishers Exact test

there has not been a study done to assess the level of

were used to test for significant associations between

adoption of this practice in health institutions in Nigeria.

proportions. Comparison of means was done with the

We

set out to determine the proportion of Nigerian

student’s t test. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered

health workers at a paediatric conference rendering pae-

statistically significant.

diatric care who practice KMC in their institution, and

identify some challenges affecting the practice of KMC

in

Nigerian health institutions.

Results

There were 157 respondents recruited in the study that

Methods

completed and returned questionnaires out of 223 ques-

tionnaires distributed giving a response rate of 70.4%.

th

A

cross sectional study of the participants at 45 annual

Of

this, 62 (39.5%) were males and 95 (60.5%) were

scientific conference of the Paediatric Association of

females giving a male to female ratio of 1: 1.5. Table 1

Nigeria held in Calabar, Nigeria in January 2014 was

shows the age group and gender distribution of the re-

conducted. The annual scientific meeting of the Pediat-

spondents.

ric Association of Nigeria is a forum that is usually at-

tended by health workers who are involved or have in-

Table 1: Age

group and

gender distribution

of respondents

terest in the care of children. Attendees are usually made

Gender

up

of doctors and nurses at different levels of their pro-

Male

Female

Total

fession practicing in and outside Nigeria. The forum is a

Age

group (years)

N

(%)

N

(%)

N

(%)

place for rubbing of minds, sharing of experiences and

solutions to problems confronting both child health spe-

<20

0

(0.0)

1

(100.0)

1

(0.6)

cialists and the Nigerian Child.

20

– 30

2

(20.0)

8

(80.0)

10

(6.4)

31

– 40

39

(50.6)

38

(49.4)

77

(49.0)

41

– 50

15

(31.2)

33

(68.8)

48

(30.6)

Nigeria is a country with 36 states divided into six geo-

51

– 60

5

(31.2)

11

(68.8)

16

(10.2)

political zones [North Central (Benue, FCT, Kogi,

>60

1

(20.0)

4

(80.0)

5

(3.2)

Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger and Plateau); North East

Total

62

(39.5)

95

(60.5)

157

(100.0)

(Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe);

North West (Kaduna, Katsina, Kano, Kebbi, Sokoto and

The respondents consisted of health practitioners prac-

Jigawa); South East (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu

ticing in 26 out of the 36 states in Nigeria. Respondents

and Imo); South South (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross-

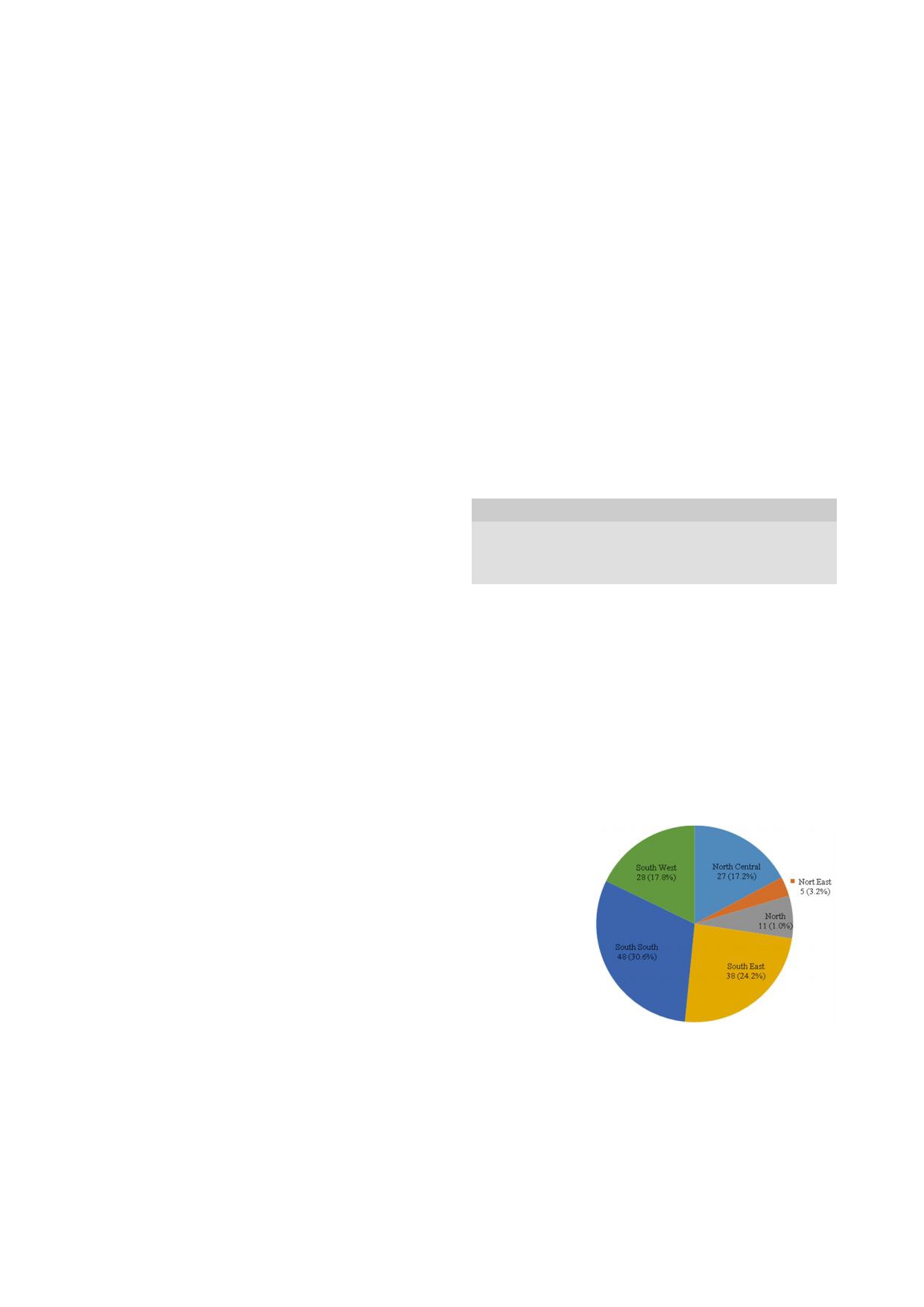

from the South – South geo – political zone were the

River, Delta, Edo and Rivers); and South West (Ekiti,

most, represented48 (30.6%) while those from the North

Lagos, Osun, Ondo, Ogun and Oyo]. This was used to

east had the least number of respondents 5 (3.2%)

categorize the location of the health facilities where the

(Figure 1).

participants practiced.

Fig 1: Distribution

Ethical clearance was obtained from the local organizing

of

respondent’s

committee of the conference. Verbal consent was ob-

health facilities by

geo

– political

tained from the attendees and questionnaires were given

zones of Nigeria

to

those that gave consent. The filled out questionnaires

were continually retrieved throughout the three days

duration of the conference. Information collected from

respondents included health facility information [name,

location, type of practice, level of care rendered, avail-

ability of neonatal care, transport incubators and ade-

quacy of incubators, and routine practice of KMC] and

Health worker information [age, gender, occupation,

level of qualification, area of specialty, years of practice,

Of

the 157 respondents, there were 122 (77.7%) doctors

personal practice experience in educating parents or

and 35 (22.3%) nurses. A total of 138 (87.9%) respon-

actual practice]. Questions on various levels of personal

dents worked in tertiary institutions and only one re-

practice of KMC by the respondents including prescrib-

spondent worked in a primary health care center. Major-

ing, teaching and giving information to parents, super-

ity of the respondents 97.3% had been practicing as

vising and assisting in provision of KMC to neonates

health care providers for more than 5 years (Table 2).

were asked in the questionnaire. Each positive answer

was scored one point and the total scores were added up.

254

Table 2: Qualification,

care level

and years

of practice

of

Table 4: Distribution

of health

workers that

practice KMC

by

Respondents

geo –

political zones

Frequency (N)

Percent (%)

Hospital Kangaroo Mother Care

Qualification

Consultant

59

37.6

practice

Senior Registrar

36

22.9

Yes

No

Total

P

Registrar

24

15.3

Geo

– political zone

N

(%)

N

(%)

N

Medical Officer

3

1.9

North Central

10

(37.0)

17

(63.0)

27

0.05

Nurse

35

22.3

North

East

0

(0.0)

5

(100.0)

5

0.02

Care level of health facility

North

West

9

(81.8)

2

(18.2)

11

0.05

Primary

1

0.6

South

East

21

(55.3)

17

(44.7)

38

0.80

Secondary

18

11.5

South South

28

(58.3)

20

(41.7)

48

0.42

Tertiary

138

87.9

South West

16

(57.1)

12

(42.9)

28

0.67

Years of practice

Total

84

(53.5)

73

(46.5)

157

<5

9

5.7

5-10

46

29.3

11-15

46

29.3

As

shown in Table 5, the level of practice of KMC

16

- 20

17

10.8

among respondents was significantly higher among

>20

39

24.9

respondents that worked in facilities that care for sick

neonates (p = 0.049), those that worked in facilities with

One hundred and four (98.1%) respondents worked in

functional incubators (p = 0.014) and those that worked

facilities that care for sick neonates and the facilities of

in

facilities that practice KMC (p < 0.001). The level of

84

(53.5%) of the respondents practiced Kangaroo

practice was also higher among females, nurses and re-

Mother Care (Table 3).

spondents that practiced in the Southern part of the

Country but the observed differences were not statisti-

Table 3: Some

neonatal care

practices of

facilities where

re-

spondents practice

cally significant. The level of practice tended to improve

with increasing years of practice except among those

Neonatal care practices of facility

Yes

N(%)

No

N (%)

that had practiced for 11 – 15 years where a slight

Care of sick newborns

154

(98.1)

3

(1.9)

decline was noted. It also tended to improve with

Availability of incubators

85

(54.1)

72

(45.9)

increasing care level of facility from Primary to Tertiary.

Availability of transport incubators

53

(33.8)

104

(66.2)

Practice of Kangaroo Mother Care

84

(53.5)

73

(46.5)

Table 5: Relationship

between level

of practice

of KMC

and

some variables

Of

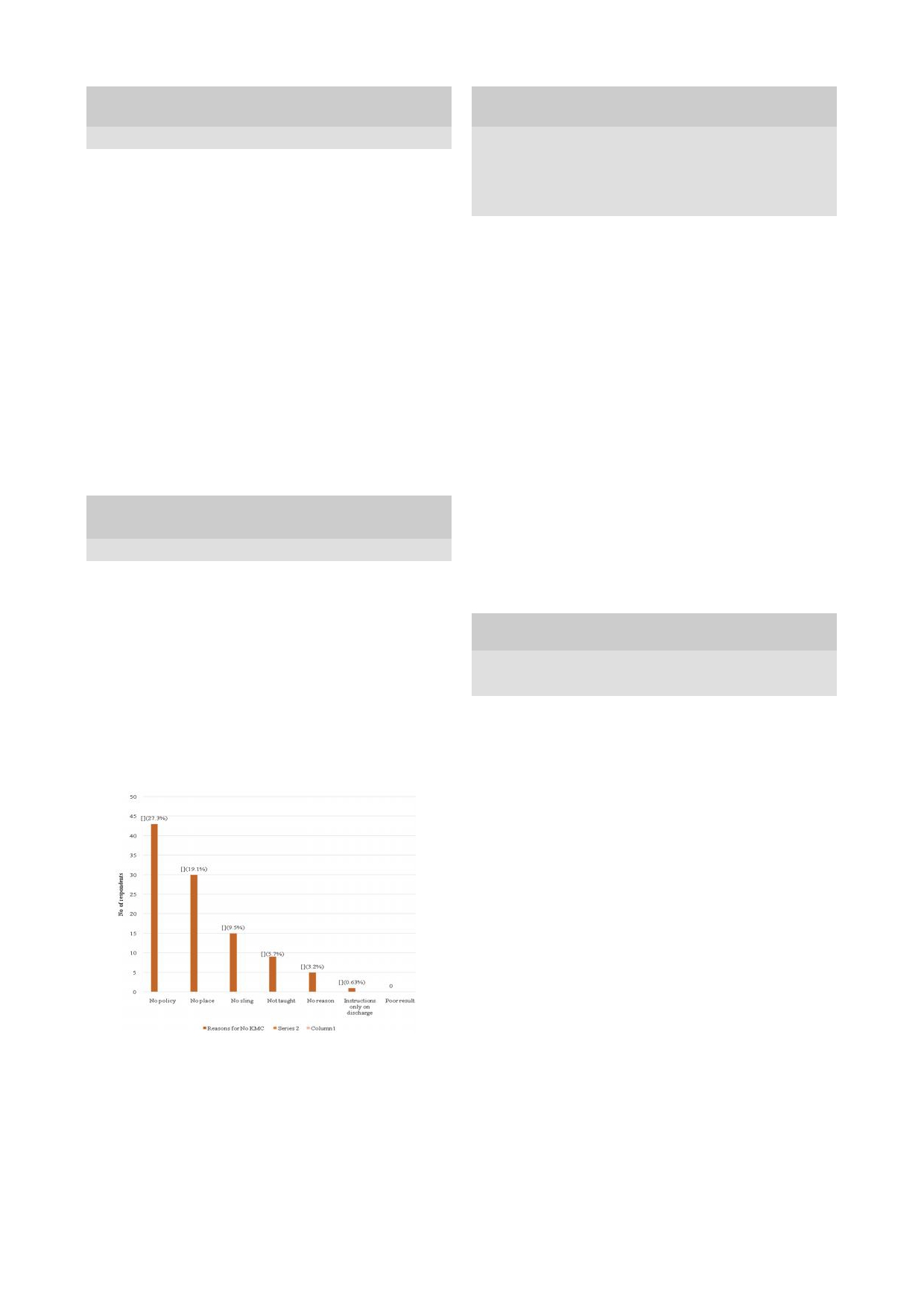

the 73 respondents that did not practice KMC in their

Level of

practice of KMC

facilities, the most common reason reported by 43

Moder-

Variable

Good

Total

P

(58.9%) was a lack of policy on the practice of KMC.

ate /

Poor

Gender

Male

34

(54.8)

28 (45

2)

62

(39.5)

0.084

No

respondent reported poor Result as a reason for not

Female

65

(68.4)

30

(31.6)

95

(60.5)

practicing KMC (Figure 2).

Occupation

Doctor

72

(59.0)

50

(41.0)

122

(77.7)

0.050

Nurse

27

(77.1)

8

(22.9)

35

(22.3)

Fig 2: Reasons

for not

practicing Kangaroo

Mother Care

in

Paediatri-

Specialty

70

(58.8)

49

(41.2)

119

(75.8)

0.052

facilities of respondents

cian

Non -

paediatri-

29

(76.3)

9

(23.7)

38

(24.2)

can

Neonatolo-

Subspecialty

16

(61.5)

10

(38.5)

26

(16.6)

0.860

gist

Non -

neonatolo-

83

(63.4)

48

(36.6)

131

(83.4)

gist

Location

of

26

(60.5)

17

(39.5)

43

(27.4)

0.679

health

facility

North

South

73

(64.0)

41

(36.0)

114

(72.6)

Care level

of

Primary

0

(0.0)

1

(100.0)

1

(0.6)

0.603

health

facility

Secondary

11

(61.1)

7

(38.9)

18

(11.5)

Tertiary

88

(63.8)

50

(36.2)

138

(87.9)

Care for

sick

Yes

99

(64.3)

55

(35.7)

154

(98.1)

0.049*

neonates

No

0

(0.0)

3

(100.0)

3

(1.9)

Availability

of

KMC was practiced most among health care facilities in

Yes

61

(71.8)

24

(28.2)

85

(54.1)

0.014*

incubators

the North West geopolitical zone (81.8%) and not at all

No

38

(52.8)

34

(47.2)

72

(45.9)

among represented facilities from the North East zone

Practice

of

<0.001

Yes

70

(83.3)

14

(16.7)

84

(53.5)

(Table 4).

KMC in

facility

*

No

29

(39.7)

44

(60.3)

73

(46.5)

Years

of

<5

4

(44.4)

5

(55.6)

9

(5.7)

practice

5 - 10

30

(65.2)

16

(34.8)

46

(29.3)

0.605

11 -

15

28

(60.9)

18

(39.1)

46

(29.3)

16 -

20

12

(70.6)

5

(29.4)

17

(10.8)

>20

25

(64.1)

14

(35.9)

39

(24.8)

255

Discussion

ter. If KMC knowledge is impacted to these primary

care centers then they can efficiently follow up the pre-

Health workers from the South South (SS) geopolitical

term infants and give support to mothers who continue

region were the most represented in our sample popula-

KMC at home. Another reason the practice needs to be

tion while the North East (NE) was the least represented.

scaled up to the peripheral centers is the absence of

The location of the conference in which the study was

transport incubators seen in 66.2% of the health centers

carried was in the SS region so this could account for its

that respondents come from which is made up of mostly

high representation. The NE however has been reported

tertiary centers. With the poor social amenities that are

to

have the lowest number of pediatricians in Nigeria

obtainable in low income countries, ambulance services

with >600,000 children per pediatrician ratio.

10

There

are almost non-existent and as such KMC is the safest,

has also been incidences of terror attacks in the past one

practical way to transport a low birth weight infant born

year in the NE region leading to displacements of people

in

a remote or peripheral health center that needs to be

inclusive of health workers. Most (87.9%) of the health

transferred to a tertiary center for specialized neonatal

workers in our study population were in tertiary centers,

care.

it

is not surprising as Ekure et al had earlier reported that

87.5% of pediatricians in Nigeria were in the tertiary

The most common reason reported for not implementing

institutions. This brings to light, the essential need for

10

KMC was not having a written protocol. Absence of

pediatricians practicing in theses tertiary centers to iden-

clear guidelines on KMC is a barrier to its implementa-

tion

12,13

tify and adopt the secondary and primary health centers

Written protocols help institutions standardize

within their locality in order to influence and impact

their practice, it enables the members of staff to be con-

positively on their practice. The pediatricians ought to

sistent at following procedures to achieve set goals with

work in the consciousness of the fact that, their responsi-

minimal errors. In the practice of KMC, having written

bility is not confined to the four walls of the tertiary

protocols would help standardize the decision of who

health facility in which they work but that it extends

qualifies for the care, where it should be carried out and

down to the grass root. This can be called "The triangu-

discharge procedure. Another factor affecting KMC

lar care” with the pediatrician in the tertiary facility at

practice in our study is not having a suitable environ-

the top of this triangle.

ment. For places where KMC has been successfully

practiced they had a dedicated KMC ward with beds for

the mothers

.3,14

In

our study 45.9% of the respondents did not have incu-

Most health facilities in low income

bators in their health facility and 66.2% did not have

countries barely have enough space for baby cots and

transport incubators. The needs that contributed to high

incubators and cannot provide a ward for stable mothers

neonatal mortality which inspired the introduction of

to

stay and practice KMC. Besides that, there is the

KMC in the early seventies is still with us, especially in

problem of transferred cost of such KMC ward occu-

low income countries and these include inadequate incu-

pancy on the family who already has the financial bur-

bators, overcrowding and the impact of mother and new-

den of a long stay preterm infant. If KMC wards are to

born separation in hospitals caring for low birth weight

be

provided, the problem of who to finance its mainte-

infants. Added to the afore mentioned, is the unavail-

1

nance would have to be addressed, at no added cost to

ability of transport incubators to transport preterm in-

the mothers practicing KMC within the hospital. In this

fants born in peripheral centers to bigger hospitals where

era of public-private partnership in Nigeria health indus-

neonatal care is available. All these highlights the need

try, KMC wards can be subsidized and charged at bi-

to

train primary health workers at the grass root on

weekly and monthly rates. Mothers that need to stay

KMC as this may be their only transportation practice

longer in KMC wards could also be given higher dis-

option for the low birth weight infant.

counts. This would, ease the financial burden on the

parents and also benefit the hospital, with improved in-

From our study only 53.5% of the health workers prac-

fant survival and patronage.

ticed KMC, considering that these health workers are

mostly from tertiary institutions and each tertiary institu-

Lack of training contributed as a reason for not imple-

tion is a referral center for other secondary and primary

menting KMC in only 9 (12.3%) of those not practicing

facilities within their regions. This apparently translates

KMC. This supports reports which states that in most

to

a large population of low birth weight infants being

low income countries training was done for most health

nursed without the benefits of KMC. Victora et al

workers in tertiary institutions where most of our re-

stressed the importance of achieving equity in KMC

spondents worked thus, accounting for the high number

of

respondents that had been trained in KMC.

6,14

delivery as groups that are left behind are often those

It

is

with the highest burden of morbidity and mortality. This

6

remarkable to note that no health worker reported that

can be said of the need for KMC which is high in the

they did not get any beneficial result from practicing

grass root and primary health care centers where most of

KMC. This could be because at this point, more than

the deliveries take place in low income countries. Stud-

four decades after development of KMC, the benefits of

ies have shown better weight gain among low birth

the practice is not in doubt among health workers. The

weight infants discharged home on KMC than those in

problem really is, implementation bottlenecks of a prac-

conventional care.

2,11

Follow up after discharge for

tice we are convinced is beneficial to children that need

LBW babies should be done in the health facility nearest

it. Another reason given for non-implementation of

to

the infant which is usually a primary health care cen-

KMC was lack of KMC support pouch. This is unfortu-

256

nate

as any soft piece of fabric, about a meter square,

facilities and community.

can

be used to support the baby on the mother’s chest

for KMC. Although, only 1% of health workers prac-

15

KMC like every clinical skill, improves with practice so

ticed KMC only on discharge, it is important to address

it

is not surprising that its level of practice was higher

the fact that this practice is not beneficial to the baby

among health workers that cared for sick neonates, those

and the institution as both parties would be short

that had functional incubators and those that were al-

changed from benefiting from the advantages of KMC

ready practicing KMC. The regular practice of KMC

early in the care of low birth weight infants. Commenc-

contributed to a relatively higher level of practice than

ing KMC only during discharge would also lead to poor

other health workers. KMC has been described as pri-

compliance rate on the part of the mother as they would

marily a nursing intervention with medical support and

not have had enough experience with KMC before being

Nurses have been described as the catalyst for KMC

implementation and practice. It is therefore not surpris-

16

discharged to continue at home.

ing

that in our study Nurses had higher level of practice

The

health workers from NW had the highest practice of

than

doctors, as they probably were more involved in the

KMC.

The reason for this may be due to the impact of

practice of KMC.

the training program embark upon by Partnership for

Reviving Routine Immunization in Northern Nigeria;

Maternal Newborn and Child Health Initiative, in which

over 260 health workers from 3 target states ( 2 in NW:

Conclusion

Katsina, Zamfara and 1 in NE :Yobe) were trained in

KMC with the mandate to implement and step down to

In

conclusion more than half of the Nigerian health

their individual states. The NW seemed to have made

8

workers that responded practiced KMC. The common

significant progress far exceeding the country’s average

reasons for not implementing KMC in our health facili-

KMC practice rate (53.5%). The NE however had the

ties were not having a written policy and not having an

lowest KMC practice rate without reflecting the benefits

adequate place for the mothers to stay.

of

the same program carried out in NW. The fact that the

We

recommend that hospitals should have a written

NE

has very few health workers as earlier stated could

KMC policy in order to successfully practice it. We also

account for its low KMC practice rate because, the im-

recommend provision of KMC wards in order to provide

plementation and stepping down of KMC at the state

a

suitable environment for the implementation of KMC

level requires health workers which the region is in short

in

our health facilities.

supply of. The overall KMC practice rate in Nigeria is

low, however, the significant progress recorded by the

Conflict of interest: None

PRRINN-MCH training program can be adopted on a

Funding: None

national level to improve KMC practice in our health

Reference

1.

Cattaneo A, Davanzo R, Uxa F.

5.

Kinney K, Lawn J, Kerber k and

8.

Aboda A, Williams A. An update

Recommendations for the Imple-

Save the Children US. Science in

technical brief: Saving Low Birth

mentation of Kangaroo Mother

Action; saving the lives of Africa’s

Weight Newborn Lives through

Care for Low Birth weight Infants.

mothers, newborns & children.

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC)

ActaPaediatrica. 1998; 87:440 – 5.

Report. African Science Academy

PRRINN-MNCH Experience

2.

Rao

Suman PN, Udani R, Nanavati

Development Initiative.2009;1.

2012;1. Available at :http://

R.

Kangaroo mother care for low

Available at http://www.who.int/

www.prrinn-mnch.org/

birthweight infants: a randomized

pmnch/topics/continuum/

documents/KMC_UPDATE

controlled trial. Indian

Pediatr

scienceinaction.pdf Accessed fe-

March2012_14.pdf. Accessed

2008;45:17-23.

buary 3, 2016.

February 3,2016.

3.

Worku B, Kassie A. Kangaroo

6.

Victora CG, Rubens CE, and the

9 .

Ajayi AO. Improving neonatal

mother care: a randomized con-

GAPPS Review Group. Global

care in Nigeria using appropriate

trolled trial on effectiveness of

report on preterm birth and still-

technology. Guest lecture at the

29

Annual general and scientific

th

early kangaroo mother care for the

birth (4 of 7): delivery of interven-

low

birthweight infants in Addis

tions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

conference of the paediatric asso-

Ababa, Ethiopia. J

Trop Pediatr

2010; 10 Suppl 1:S4.

ciation of Nigeria in Ilorin,

2005;51:93-7.

7.

Pattinson RC, Arsalo I, Bergh AM,

Kwara State, Feb 1998.

4.

Lawn JE, Mwansa-Kambafwile J,

Malan AF, Patrick M, Phillips N.

10. Ekure

EN, Esezobor

CI, Balogun

Horta BL, Barros FC, Cousens S.

Implementation of kangaroo

MR,

Woo JG, Mukhtar-Yola M,

Kangaroo mother care’ to prevent

mother care: a randomized con-

Ojo

OO et al. Paediatrician work-

neonatal deaths due to preterm

trolled trial of two outreach strate-

force in Nigeria and impact on

birth complications. Int.

J. Epide-

gies. Acta

Paediatr. 2005;94

child health: Niger

J Paediatr

miol. 2010;39Suppl 1: i144-i154.

(7):924-97.

2013; 40 (2): 112 – 118.

257

11.

Nguah BS, Wobil PNL, Obeng R,

13.

Seidman G, Unnikrishnan

15.

World Health Organisation. Kan-

Yakubu A, Kerber KJ, Lawn JE, et

S,

Kenny E, Myslinski S, Cairns-

garoo mother care: a practical

al

Perception and practice of Kan-

Smith S, Mulligan B, et alBarriers

guide. Geneva, Switzerland:

garoo Mother Care after discharge

and

enablers of kangaroo mother

Department of Reproductive

from hospital in Kumasi, Ghana: A

care practice: a systematic review.

Health and Research World

longitudinal study. BMC

Preg-

PLoS One 2015; 10(5).

Health Organization ; 2003.

nancy Childbirth. 2011; 11: 99.

14.

Solomons N, Rosant C. Knowl-

16.

Davy K, Van Rooyen E. The

12.

Bergh AM, Arsalo I, Malan AF,

edge and attitudes of nursing staff

neonatal nurse’s role in kangaroo

Patrick M, Pattinson RC, Phillips

and

mothers towards kangaroo

mother care. Prof

Nurs To-

N.

Measuring implementation

mother care in the eastern sub-

day.2011;15(3):32-37.

progress in kangaroo mother care.

district of Cape Town. S

Afr J

Clin

ActaPaediatr 2005;94:1102-8.

Nutr 2012;25(1):33 -39.