Copyright 2015 © Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. All Rights Reserved. . Powered by Pelrox Technologies Ltd

ISSN 03 02 4660 AN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA

Quick Navigation

Niger J Paediatr 2016; 43 (4): 291 – 294

CASE

REPORT

Ekanem EE

Ulcerative colitis in a Nigerian

Ikobah JM

Ngim OE

child: case report

Okpara HC

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i4.11

Accepted: 2nd June 2016

Abstract :

Ulcerative colitis

(UC)

diagnosis. An 11 year old Nigerian

is

a chronic re-occuring inflam-

male child who was referred to the

Ekanem EE

(

)

matory disease affecting mainly

University of Calabar Teaching

Ikobah JM, Ngim OE

the colon. It is more prevalent in

Hospital with bleeding per rectum,

Okpara HC

Department of Paediatrics,

the

United

Kingdom,

North

abdominal pain and swelling, bilat-

University of Calabar/University of

America Scandinavia and less

eral leg swelling and weight loss

Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar,

common in southern Europe, Asia

for seven months prior to presenta-

Cross River State, Nigeria

and Africa. Commonly, UC is

tion. Examination and investiga-

Email:

suspected in patients presenting

tions done including colonoscopy,

emmanuelekanem@unical.edu.ng

with bloody diarrhoea, tenesmus,

histology of biopsy, faecal calpro-

abdominal pain, and, when se-

tectin and pANCA confirmed ul-

vere, weight loss, fatigue, and

cerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis

vomiting. Perhaps one child so far

though rare in Africa may have

with UC has been reported south-

been missed in some children due

west geo-political zone of Nige-

to

mis-conception and lack of di-

ria. We here report the first case

agnostic facilities/expertise. We

of

ulcerative colitis in a child in

may begin to see more of this with

south-south Nigeria.

increasing interest in the sub-

The objective of this report was to

specialty of paediatric gastroen-

highlight the occurence of ulcera-

terology and presence of diagnos-

tive colitis in a Nigerian child in

tic facilities.

the

setting

of

poor

socio-

psychological/economic

back-

Key word: Ulcerative

Colitis,

ground coupled with difficulty in

Diagnostic difficulties, Nigerian

investigating patient to arrive at a

child

Introduction

tenesmus, abdominal pain, and, when symptoms become

severe, weight loss, fatigue, and vomiting. Children

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic re-occuring inflam-

have unique age-related considerations, such as growth,

matory condition of the colon, extending continuously

puberty, nutrition, and bone mineral density (BMD)

from the rectum proximally to a varying degree. Most

accretion during adolescence, as well as differing psy-

chosocial needs and development.

7,8

children with

ulcerative colitis present between the ages

of 10 and 18

years. The

incidence of

pediatric-onset

1,2

Ulcerative colitis is thought to be rare in sub-Saharan

UC, forms roughly 15% to 20% of patients of all ages

Africa, however, in Nigeria, ulcerative colitis has been

reported in adults.

9,10

with UC, ranging between 1 and 4 of 100,000/year in

It

was also reported in a seven year

Children

old female child in south-west Nigeria.

11

most North American and European regions.

1-3

We

report a

and adults develop

similar symptoms however children

confirmed case of ulcerative colitis in an 11 year old

often present with more

extensive disease. Childhood-

[4]

child in south-south Nigeria.

onset UC is extensive in 60% to 80% of all cases, twice

as

often as in adults with 82% of children at first pres-

4

Case report

entation have a pancolitis compared to 48% of adults.

5

The

extent of the disease is associated with disease se-

This

was an 11 year old adolescent male who presented

verity, therefore, most pediatric-onset UC have a worse

to

the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar,

disease course. The pathogenesis of

ulcerative colitis is

6

Cross River State, Nigeria with history of bleeding per

unknown. A widely

accepted hypothesis suggests that,

rectum, abdominal pain, abdominal swelling and weight

in the genetically

susceptible individual, a combination

loss

of seven months duration. Patient’s stool was mixed

of host and environmental

factors lead to the initiation

with

fresh blood. Abdominal swelling was insidious in

and perpetuation of an

abnormal intestinal immune re-

onset and gradually increased over time. There was as-

sponse, resulting in

Ulcerative colitis. Typically, UC

is

sociated history of abdominal pain which was dull and

suspected in a patient presenting with bloody diarrhoea,

continuous in nature. There was a positive history of

292

vomiting and easy satiety. There was a positive history

ence of 5-6 RBC per hpf. Echo- cardiography result was

of

weight loss and fever. Leg swelling occurred at same

normal. Hepatitis B and C screening was negative and

time as abdominal swelling. There was history of dysp-

HIV test was also negative. Summary of findings of

noea on exertion, no orthopnoea or paroxysmal noctur-

abdominal ultrasound scan using a 3.5MHz curvilinear

nal dyspnoea. He was given herbal preparation as en-

probe includes mild enlarged and coarse looking liver

ema in a herbal home. He also received treatment from a

with caudate lobe enlargement, minimal ascites and

secondary health facility from where he was referred to

splenomegaly, gall bladder enlargement and increase in

the UCTH. Patient is the second child in a family of

wall thickness but no convincing evidence of portal hy-

two. Parents are separated and patient lives with the

pertension.

grandfather, a peasant farmer.

C

– reactive protein assay was within normal limit.

On

examination he was acute on chronically ill looking,

Liver biopsy was not done due to the deranged INR.

conscious, wasted, small for age, a febrile, severely pale,

Faecal calprotectin result was 155.57mg/kg faeces( bio-

jaundiced with bilateral pitting pedal oedema. Respira-

logical reference interval <25mg). Peri-nuclear anti neu-

tory

rate was 32cycles/minute, chest was clinically clear,

trophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA) was positive.

pulse

rate

was

88/minute,

blood

pressure

was

Upper and lower GI endoscopy was done and samples

I00/60mmHg, heart sound was SI and S2. Patient had a

taken for histology and cytology. Both the faecal calpro-

grossly distended abdomen with tenderness over the

tectin and p-ANCA assay were done in India as we

right and left hypochondria, liver was enlarged by 8cm

could not find a local laboratory that could perform the

below the right costal margin firm, tender, nodular, with

test. Upper GI endoscopic findings were normal with no

poorly defined edge. The spleen was 6cm enlarged be-

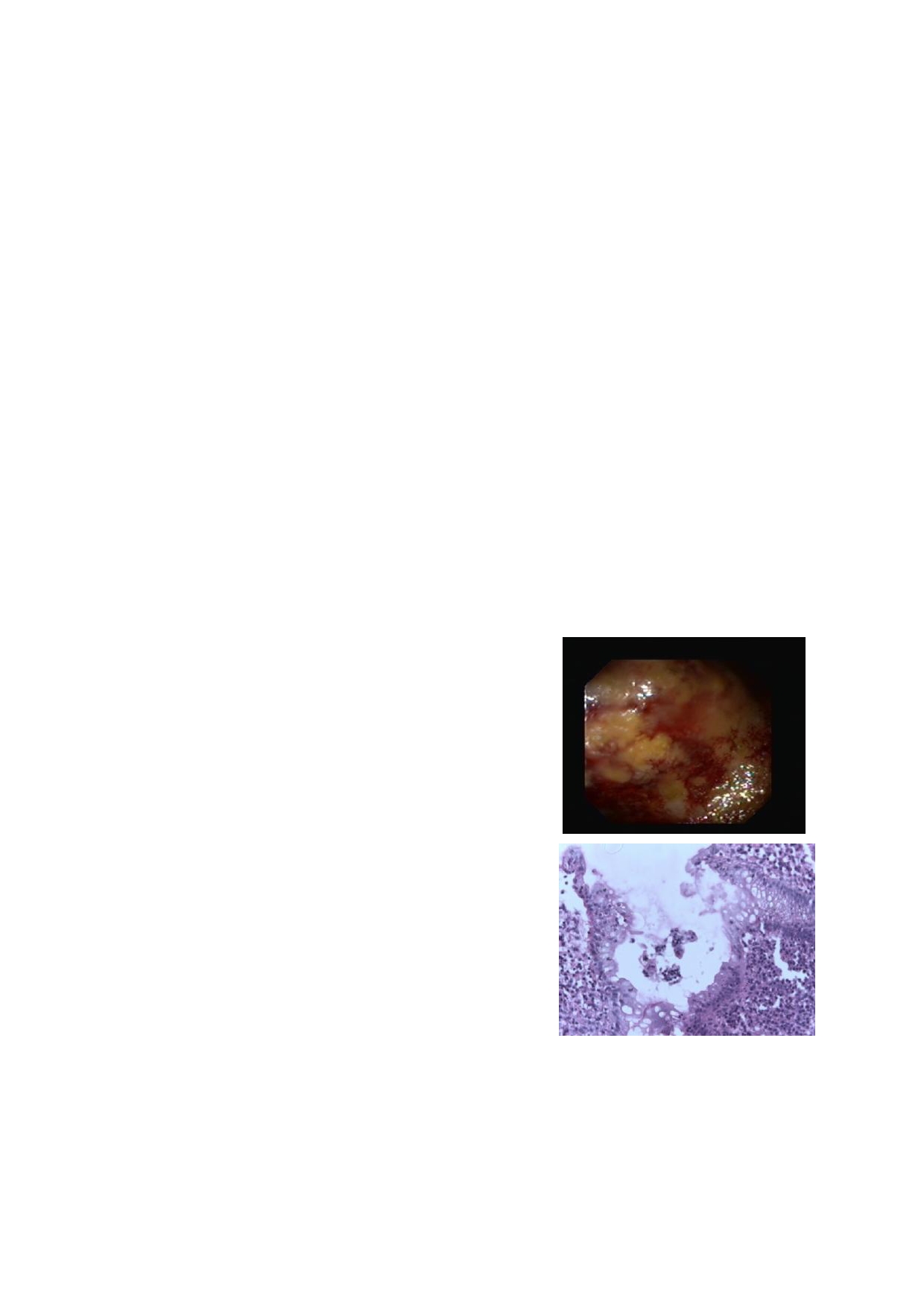

evidence of varices. Colonoscopy showed extensive

low the left costal margin, firm, smooth, non tender.

haemorrhagic mucosa of the large bowel all the way to

Fluid thrill was demonstrable. Rectal examination re-

the transverse colon (Fig. 1). Lesions were worse in the

vealed good anal hygiene, anal tags present at 4 o’

rectosigmoid

area. No ulcers, polyps, diverticular or

clock, 7 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions, normal

tumour were seen and no haemorrhoids . Cytology was

sphincteric tone, no palpable rectal masses. Examining

negative for malignancy and histology result showed

finger stained with feaces mixed with blood. An initial

chronic non-specific cololitis (Fig. 2). The activity of

diagnosis of chronic liver disease was made.

UC

using the paediatric ulcerative colitis activity index

(PUCAI) for the index patient was a score of 45 giving

him a moderate disease at diagnosis.

Results

Fig 1

Packed cell volume ranged between eight percent and

19%, patient was transfused four times while on admis-

sion. Full blood count showed total white cell count of

5.8%, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 55mm/hr

(Westergren method), neutrophil of 67%, lymphocyte of

33%,

evidence of aniscocytosis, microcytosis, hy-

pochromasia and poikilocytosis. Liver function test done

showed total bilirubin of 58umol/l (normal range of 0.0-

17.0 ), direct bilirubin of 45.5umol/ (normal range of 0.0

-6.8 ), indirect bilirubin of 12.8umol/l (normal range of

0.0-10.3), alanine aminotransferase/SGPT of 41.0U/L

(normal range of 0-40 ), aspartate transferase/SGOT of

Fig 2

80.0U/L (normal range of 0-37 ), alkaline phosphatase

of

753U/L (normal range of 245-770), total protein of

57g/L(normal range of 55.0-82.0 ), albumin of 34g/L

(normal range 37.0-53.0 ), globulin of 23g/L (normal

range 15.0-36.0), GGTP 243.4U/L (normal range 10.0-

71.0). C-reactive protein level was within normal limit.

Lipid profile showed total cholesterol 3.6mmol/l

(normal range 3.6-5.2), HDL Cholesterol 1.6mmol/l

(normal range of 0.9-1.5), LDL Cholesterol 0.7mmol/l

(normal range of 1.9-3.5), triglyceride 2.9mmol/l

(normal range of 0.6-1.7). Initial prothrombin time was

30.5 seconds (prothrombin control 15 second), interna-

Discussion

tional normalized ratio (INR) of 2.13. A repeat done

after vitamin K administration showed prothrombin time

UC

is known to occur globally though less common in

was 23.6 second (prothrombin control 15 second), inter-

Africa and especially sub-Saharan Africa. This could be

national normalized ratio of 1.65. Stool microscopy,

due to lack of diagnostic expertise and the fact that there

culture and sensitivity result was normal except for pres-

is

still a high burden of infective diseases to battle with

293

and

the thought of UC commonly seen as a westernized

Presently, there is no permanent medical cure for UC.

illness is far from it. However, with increasing interest

The general goals of treatment in children are to control

in

gastroenterology as a sub-specialization and improv-

symptoms of the disease with minimal adverse effects of

ing expertise, few cases has been reported in adults in

the medicines used and to achieve normal functioning of

13

Uganda.

14

Ghana South Africa,

12

Nigeria

9,10

UC

has

the

patient. The intensity of treatment is dependent on

also

been reported in a seven year old Nigerian child

the

severity of the disease. Patients with moderate ul-

but

without the current diagnostic investigations of en-

cerative colitis are usually treated on an outpatient basis.

doscopy, faecal calprotectin and P-ANCA to confirm

However our patient was admitted on account of severe

this

hence our patient is the first confirmed case of UC

anaemia, poor socio-economic background and dysfunc-

in

a paediatric patient in Nigeria.

11

tional home setting. After initial stabilization, he was

started on pediatric medical regimen with low residue

As

in other reported cases in Africa, the diagnosis of UC

diet and prednisolone. Two days into commencement of

in

our index patient was not thought of initially at first

therapy, blood in stool stopped, appetite improved and

presentation. Patient was treated for dysentery and with

patient became more ambulatory. However compliance

persistence of passage of bloody diarrhoea, deranged

to

medication was poor due to the dysfunctional home

liver function test and the need for recurrent blood trans-

setting. This was also reported as affecting treatment

success in the first reported case in Nigeria

11

fusion, patient had a colonoscopy with biopsy done and

UC

was confirmed. This therefore underscores the need

for a high index of suspicion even in African children

Patient has been lost to follow-up despite repeated

with chronic bloody diarrhoea, weight loss and recurrent

phone calls. This is commonly the case in patients with

anaemia. Cabrera-Abreu showed a diagnostic sensitiv-

14

chronic illnesses and even worse in children who have

ity and specificity of 90.8% and 80% respectively in

to

rely on adult caregiver. This has been reported in Ni-

gerian adults

9,10

patients with signs suggestive of IBD and existence of

with UC and in the Nigerian child with

UC. Late presentation to hospital is a major problem in

11

anaemia or thrombocytosis. In children with UC, blood

loss could occur in 84%, diarrhoea in 74% and abdomi-

sub-Saharan Africa. Patients patronize alternative medi-

nal pain in 62% of patients. Weight loss is less com-

15

cal practitioners as was the case in our patient before

mon in UC (35%) than CD (58%).

15

Our patient pre-

presenting to the hospital as a last resort. Delay or fail-

sented with all these symptoms. Extra-intestinal mani-

ure of diagnosis of IBD may also result from lack of

festations of IBD may be present in 25% to 35% of

awareness, denial of the presence of IBD by our physi-

children.

15

Our patient presented with perianal disease

cians and limited facilities for most of the key investiga-

(skin tags) and hepatic disease. Hepatic

abnormalities in

tions in our environment.

18-20

Paediatric endoscopy only

started recently in Nigeria.

19,20

children with

ulcerative colitis have been well de-

Perhaps with increasing

scribed.

16

While these are

typically identified after the

use of endoscopic diagnostic facilities, more cases of

ulcerative colitis

diagnosis, they may also precede the

IBD in children will be discovered.

gastrointestinal

symptoms.

16

Transient elevations

of

alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) occur in 12% of chil-

dren with ulcerative

colitis and appear to be related to

medications or disease

activity. Persistent ALT eleva-

Conclusion

tions suggest the

presence of primary sclerosing

cholangitis (PSC) or

autoimmune chronic hepatitis.

17

Ulcerative colitis is reported in a sub-Saharan African

Among children with

ulcerative colitis, 3.5% develop

child. Though this appears rare, mis-diagnosis and mis-

sclerosing cholangitis

and less than one percent develop

conception of its rarity in African children may have

chronic hepatitis. The

diagnosis of PSC may be sus-

accounted for lack of reports on this inflammatory dis-

pected based on

symptoms of chronic fatigue, anorexia,

ease in Africa.

pruritus or jaundice,

although many children may be

asymptomatic. The

diagnosis of PSC may be established

through a combination

of cholangiography and liver

Conflict of interest: None

biopsy. Our patient

could not have a liver biopsy done

17

Funding: None

due to deranged INR and

cholangiograpghy was far

reached.

Reference

1.

Mendeloff AI, Calkins BM. The

2.

Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Goz-

3.

Chong SK, Blackshaw AJ,

epidemiology of idiopathic inflam-

dyra P, Meta Van den Heuvel,

Morson BC, Williams CB,

matory bowel disease. In Kirsner

Johan Van Limbergen, Griffiths

Walker-Smith JA. Prospective

JB,

Shorter RG, eds. Inflamma-

AM.

Epidemiology of pediatric

study of colitis in infancy and

tory Bowel Disease.

Philadelphia:

inflammatory bowel disease: a

early childhood. J

PediatrGastro-

Lea &Febiger, 1988: 3 – 34.

systematic review of international

enterolNutr1986; 5(3): 352 – 358.

trends. Inflamm

Bowel Dis

2011;

4.

Gryboski JD. Ulcerative colitis in

17:423 – 439.

children 10 years old or younger.

J PediatrGastroenterolNutr1993;

17: 24 – 31.

294

5.

Mamula P, Telega GW, Markowitz

11.

Senbanjo IO, Oshikoya KA, On-

17.

Roberts EA. Primary sclerosing

JE,

Brown KA, Russo PA, Piccoli

yekwere CA, Abdulkareem FB,

cholangitis in children. J

Gastro-

DA

et al. Inflammatory bowel

Njokanma OF. Ulcerative colitis

enterolHepatol1999; 14: 588 –

disease

in children 5 years of age

in

a Nigerian girl: A case report.

593.

and

younger. Am

J Gastroen-

BMC

Research Notes 2012 5:564.

18.

Ekwunife CN, Nweke IG, Achusi

terol2002 Aug; 97(8): 2005 – 2010

12.

Nkrumah KN. Inflammatory Bowel

IB,

Ekwunife CU. Ulcerative

6.

Langholz E, Munkholm P, Krasil-

Disease at the Korle Bu Teaching

colitis prone to delayed diagnosis

nikoff PA, Binder V. Inflammatory

Hospital, Accra. Ghana

Med J.

in

a Nigerian population: Case

bowel diseases with onset in child-

2008 Mar;42(1):38-41

series. Ann

Med Health

Sci Res.

hood. Clinical features, morbidity,

13.

Segal I, Tim LO, Hamilton DG,

2015 Jul-Aug; 5(4):311-313

and

mortality in a regional cohort.

Walker AR. The rarity of ulcera-

19.

Ngim OE, Ikobah JM, Ukpabio I,

Scand J Gastroenterol1997 Feb;

tive colitis in South African blacks.

Bassey GE, Ekanem EE. Paediat-

32(2): 139 – 147.

Am J Gastroenterol. 1980 Oct; 74

ric

Endoscopy in Calabar, an

7.

Van

Limbergen J, Russell RK,

(4):332-336

emerging trend-Challenges and

Drummond HE, Aldhous MC,

14.

Billinghurst JR, Welchman JM.

prospects: A report of two cases.

Round

NK, Nimmo ER et al. Defi-

Idiopathic ulcerative colitis in

IOSR J.

Dental and

Medical

nition of phenotypic characteristics

African: a report of four cases.

Sciences. 2014 ;13(1):28-30

of

childhood-onset inflammatory

Brit.med.J. 1966;1:211-213

20.

Ikobah JM, Ngim OE, Adeniyi F,

bowel disease .

Gastroenterol 2008

15.

Sandhu Bk, Fell JME, Beattle RM,

Ekanem EE, Abiodun P. Paediat-

Oct; 135(4): 1114-22

Mitton SG. BSPGHAN Guidelines

ric

Endoscopy in Nigeria-humble

8 .

Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel

for

the management of inflamma-

beginning. Nig

J Paed.

2015;42

disease: etiology and pathogenesis.

tory bowel disease in children in

(2):147-150

Gastroenterol1998; 115: 182 – 205.

the

United Kingdom. 2008 Oct pp

9.

Ukwenya AY, Ahmed A, Odigie

1-36.

VI,

Mohammed A. Inflammatory

16.

Hyams J, Markowitz J, Treem W.

bowel disease in Nigerians: Still a

Characterization of hepatic abnor-

rare diagnosis? Annals

of Afr

Med

malities in children with inflamma-

2011; 10( 2):175-179

tory bowel disease. Inflamm

Bowel

10.

Alatishe OI, Otegbayo JA, Nwosu

Dis1995; 1: 27.

MN,

Lawal OO, Ola SO, Anyanwu

NC

et al. Characteristics of inflam-

matory bowel disease in three

tertiary health centres in sothern

Nigeria. West

Afr J

Med.2012 Jan-

Mar;31(1):28-31