Copyright 2015 © Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. All Rights Reserved. . Powered by Pelrox Technologies Ltd

ISSN 03 02 4660 AN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA

Quick Navigation

Niger J Paediatr 2017; 44 (1): 7 – 13

ORIGINAL

Adam VY

Prevalence and comorbidities of

Isah IA

childhood overweight and

obesity among school aged

children in an urban settlement

in Benin City, Nigeria

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v44i1.2

Accepted: 6th December 2016

Abstract :

Background:

The

weight respondents was 7.7% and

prevalence of childhood over-

3.1% for obesity giving a com-

Adam VY (

)

weight and obesity is rising

bined proportion of 10.8% while

Department of Community Health

worldwide and its impact span-

that for underweight was 11.8%

Isah JA

ning through adolescence to adult-

amongst the study respondents.

Department of Child Health

hood.

The females, 18 (16.6%) had a

University of Benin Teaching Hospital

Objectives: This

study aimed

to

significantly higher proportion of

Benin City Nigeria.

determine the prevalence of over-

overweight and obesity than the

Email: Vincent.adam@uniben.edu.ng

weight and obesity and the occur-

males, 3 (3.5%) [p = 0.003]. The

rence of high blood pressure and

prevalence of hypertension was 6

elevated blood glucose among

(3.1%) and elevated blood glucose

school aged children in an urban

was 4 (2.1%).

settlement in Benin City, Nigeria.

Conclusion: The

prevalence of

Design: A

cross-sectional, de-

overweight was 7.7% while that

scriptive study was utilized.

for obesity was 3.1%. Also, the

Subjects and setting: A total of

prevalence of hypertension and

195 school aged children residing

elevated blood glucose was 3.1%

in

households in the selected ward

and 2.1% respectively amongst the

were recruited for the study car-

school aged children and females

ried out between 2014 and 2015.

had a significantly higher propor-

Outcome measures: Anthropom-

tion of overweight and obesity

etric measurements were recorded

than males in the study. There is a

and used to determine the body

need for public enlightenment to-

mass indices (BMI) of the chil-

wards promoting healthier lifestyle

dren. Also blood pressure meas-

choices and screening of disease

urements and random blood sug-

conditions early in childhood.

ars of the respondents were deter-

mined to ascertain the blood pres-

Keywords: Prevalence,

Comor-

sure

and glycaemic status of the

bidities, Overweight and obesity,

children.

School aged children, Nutritional

Results: The

proportion of

over-

status.

Introduction

There is a global increase in the prevalence of over-

weight and obesity. The worldwide prevalence has dou-

Obesity has been recognized for thousands of years as

bled between 1980 and 2014, at present 35% of adults

>20 years are overweight with 11% obese. In 2012,

[]

seen in Stone Age Statues that depicted the excessive

roundness of the female human form. Hippocrates first

about 40 million children < 5 years were OWOB and the

pointed out the possible negative health effects of obe-

prevalence was 30% higher in developing countries than

in

developed countries.

5

sity when he observed that very fat individuals were

more likely to die from sudden death than thin individu-

als. It was commonly held belief that the heavier a

1

The children who are OWOB face the twin burden of

child, the healthier he was, in order words ‘the bigger

diseases in childhood as well as increased morbidity and

the

better’. This attitude began to change by the late 19

th

mortality in adulthood. In childhood, they often have

century and has continued to the present time with in-

breathing difficulties, increased risk of fractures, hyper-

creasing recognition of the associated health risks of

tension and psychological problems while in adulthood

overweight and obesity (OWOB).

2,

they have a higher risk of premature deaths, disability

8

and obesity. The problem of OWOB in children is sig-

6

The calculated minimum sample size was 155, with an

nificant because of the associated health burden on the

addition of 16 (non-response rate of 10%), 171 was ob-

child and its implication on the health of the future adult

tained as the sample size. For the purpose of this study

population.

7

195

school aged children were recruited.

In

the United States (US), the third National Health and

Nutrition Surveys (NHANES) showed that there have

8

A

cluster sampling technique was utilized for this study.

been

increases of OWOB in all age groups and across

The

urban settlement is divided into two by a major road

both

gender over a period of 20 years from the

on

which the LGA secretariat is located. The area on the

NHANES II and NHANES III and that girls were more

left of the major road was selected by simple random

affected than boys. A similar increase was also reported

sampling through balloting and this formed a cluster. In

in

Japan where the frequency of obese school children

the selected area, a total of 332 houses were enumerated

between the ages of 6-14 years increased from 5% to

consisting of 525 households. Those households that the

10% from 1974 to 1993.

9

parents gave their permission and who had children that

met the inclusion criteria were selected for the study. A

In

a related study done to determine the prevalence of

total of 195 children were selected for the study.

OWOB using data on 720 children aged 6-18 years in

The tool for data collection was a researcher-

Ile-Ife, Nigeria. The results showed that 2.8% and 0.8%

administered structured questionnaire, pre-tested in Isio-

were overweight and obese respectively. Females were

hor community in Ovia North-East LGA, Benin City.

more likely than males to be obese.

10

Similar findings

The

questionnaire also contained details of the physical

were

obtained in another study conducted in Calabar,

examination of the children including their weights,

Nigeria, among 1,005 children and adolescents aged 6-

heights, BMI, blood pressure and random blood sugar.

18

years resident within the state. The results showed

Research assistants comprised of four doctors and four

that

the prevalence of obesity was 2.3% in the children

final year medical students who were trained on how to

aged

6-12 years. The BMI was higher in females than in

obtain information using the questionnaire and carry out

the

males. A related study was done in the three sena-

11

anthropometric measurements. This was done in order to

torial districts in Benue State to assess the demographic

ensure reliability of the information and the measure-

variation in the prevalence of OWOB using 3240 chil-

ments obtained.

dren aged 9 to 16 years. The results showed that 88.5%

had normal weights, 9.7% were overweight and 1.8%

Measures

were obese. Females (20.3%) were more likely to be

overweight than boys (16.2%).

12

The

heights of the respondents were measured using a

stadiometer. The children pulled off their footwear and

stood on the stadiometer (Axiom RGZ – 160) accord-

®

There

is a dearth of information on the prevalence and

comorbidities of childhood overweight and obesity in

ing to the National Health and Nutrition Survey

(NHANES) protocol.

[16]

school aged children within Nigeria and particularly in

Also, the weights of the children

Benin City. This study hopes to assess the presence of

were measured with their normal household wears only.

OWOB and associated comorbidities among school

They were asked to empty their pockets, pull off sweat-

aged children in Egor Local Government Area, Edo

ers

or vests, belts and wrist watches and void before

having their weights taken.

[16]

State. The information derived from this study would

The

children were

weighed using a Seca

®

therefore

add to the available data on childhood over-

digital

electronic scale (Seca

weight and obesity and may contribute to the formula-

gmbh & Co, Germany) with a calibration of 0.1kg. The

tion of health related policy at the school and Local

Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the for-

mula, BMI= Weight (Kg) / Height (m ). Blood pres-

2

2

Government level.

sures were also taken with the children sitting in a com-

fortable chair using a mercury sphygmomanometer us-

ing

standard procedures.

17

The

blood pressure was

Material and methods

measured twice and the mean value calculated and re-

corded for each child.

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in

Uselu, an urban settlement and headquarters of Egor

In

addition, the blood sugars were determined using

Accucheck blood sugar kit. The thumbs of the children

®

Local

Government Area (LGA) in Benin City, Nigeria.

Egor LGA which is one of the four LGAs making up

were cleansed with an alcohol swab, and pricked with an

Benin City comprises of 10 political wards. The LGA

individual sterile lancet. A drop of blood was applied to

has an estimated population of 420,643 people, with

the test strip and the blood sugar read off the screen of

220,226 children aged <15years (2014 estimated popu-

the

meter. The instrument was standardized using the

lation).

13

The

study participants included school aged

code strip standard that came with the kit. The kit was re

children (6-12 years) residing in households within the

-standardized after every 30 readings or before each

selected houses in the study area.

day’s activity whichever came first. The values obtained

The minimum sample size for the study was determined

were documented. A parent/care giver was present dur-

using the Cochran formula for simple proportion. n =

14

ing the examinations.

z

pq/d where p = 11.4% (proportion of overweight Ni-

2

2

gerian children in a study carried out in Uyo, Nigeria.

15

9

Data analysis

Results

The data was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 21.0

A

total of 195 children were surveyed. More than half,

(SPSS for Window Inc; Chicago, LL, USA) Statistical

109 (55.9%) of the respondents were females. The mean

software and the WHO Anthroplus . The socio-

®

age

of the children was 8.6(± 2.0) years with 96 (49.2%)

economic class was obtained using the protocol devel-

of

them aged between 6-8 years. Majority, 117 (60.0%)

oped

by Olusanya et al. The purchase and consumption

18

of

the participants were in the lower socio-economic

of

sugar sweetened beverages was grouped into

class, with 189(96.9%) being Christians. About a tenth

"often" (if consumed at least three times weekly) and

21(10.8%) were from extended families and136 (69.7%)

"rarely" (if consumed at most once monthly). The age

were Benin. Table 1

was summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD),

while the age-groups and BMI category of the respon-

Table 1: Socio-demographic

characteristics of

the respondents

dents were represented as proportions. Fisher’s exact

Socio-demographic

Frequency

Percent

test was utilized to determine association with level of

characteristic

(N

= 195)

(%)

significance set at p ≤ 0.05.

Age group (years)

6-8

96

49.2

The BMI of the respondents was further classified using

9-10

59

30.3

the WHO Growth Reference for school-aged children

11-12

40

20.5

and

adolescents according to their age and gender.

19

The respondents with BMI < -2SD for age and sex

Gender

(thinness and severe thinness) were classified as under-

Male

86

44.1

weight, between the ≥ -2SD to ≤ 1SD were classified as

Female

109

55.9

normal; >1SD were classified as overweight; while >2

Socioeconomic class

SD

were classified as obese.

Upper

21

10.8

The

mean blood pressure of the respondents were classi-

Middle

57

29.2

fied using the standard chart for age, sex and height.

20

Lower

117

60.0

The values ≤ 95 percentile were classified as normal, >

th

Ethnicity

95

percentile was classified as hypertension. The ran-

th

Benin

136

69.7

dom blood sugar values were classified thus: ≤ 140 mg/

Igbo

20

10.3

dl

as normal and > 140 mg/dl as elevated.

Esan

15

7.7

Isoko

11

5.6

Ethical considerations

Urhobo

8

4.1

Yoruba

5

2.6

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics and Re-

Religion

search Committee of the University of Benin Teaching

Christian

189

96.9

Hospital (UBTH) [protocol number ADM/E22/A/VOL

Muslim

6

3.1

VII/1141].

Also, permission was obtained from the

Heads of the communities within the selected EAs and

Family Type

the parents/ guardians of each of the selected children.

Nuclear

174

89.2

Assent was obtained from children older than 8 years of

Extended

21

10.8

age. The children who had abnormalities detected

(elevated blood pressure and blood sugar) were referred

Most, 160(82.1%) of the respondents took snacks in-

to

the Paediatric Cardiology and Endocrinology Units of

between meals and 139(71.3%) had pastries as the

UBTH respectively. The underweight and overweight/

snack. Only, 3(1.5%) of the respondents took either

obese children were referred to the Paediatric Gastroen-

fruits or groundnut (legumes) and majority, 129(66.2%)

terology/ Nutrition Unit of the same hospital for man-

had snacks once or twice daily. Sugar sweetened bever-

agement and follow-up after educating them on adequate

ages were bought in 81(41.5%) of the homes of the

nutrition and importance of physical activities. All data

respondents. Table 2

obtained were treated with utmost confidentiality.

Of

the 195 respondents, 151(77.4%) had normal BMI,

Limitations

while, 15(7.7%) and 6(3.1%) were overweight and

obese respectively. Also, 23(11.8%) who were under-

Some of the information obtained from the children may

weight. Almost all the respondents, 189(96.9%) and 191

have been subject to bias from recall and self-reporting.

(97.9%) were normotensive and normoglycaemic re-

In

addition, the blood sugar obtained from the respon-

spectively. The prevalence of hypertension and elevated

dents was a random blood sugar instead of fasting blood

blood sugar was 4(3.1%) and 2(2.1%) respectively.

sugar or 2hr post prandial (2hrPP) which would have

There was no significant difference in association be-

been a better marker of the glycaemic status of the

tween the glycaemic status of the respondents and the

school aged children. However, this would have been

BMI classification of the respondents (p = 1.000). How-

difficult to obtain in a community study.

ever, an equal proportion, 3(50.0%) of the respondents

with elevated blood pressure were overweight or had

normal weights. This association between the elevated

10

blood pressure and BMI of the respondents was statisti-

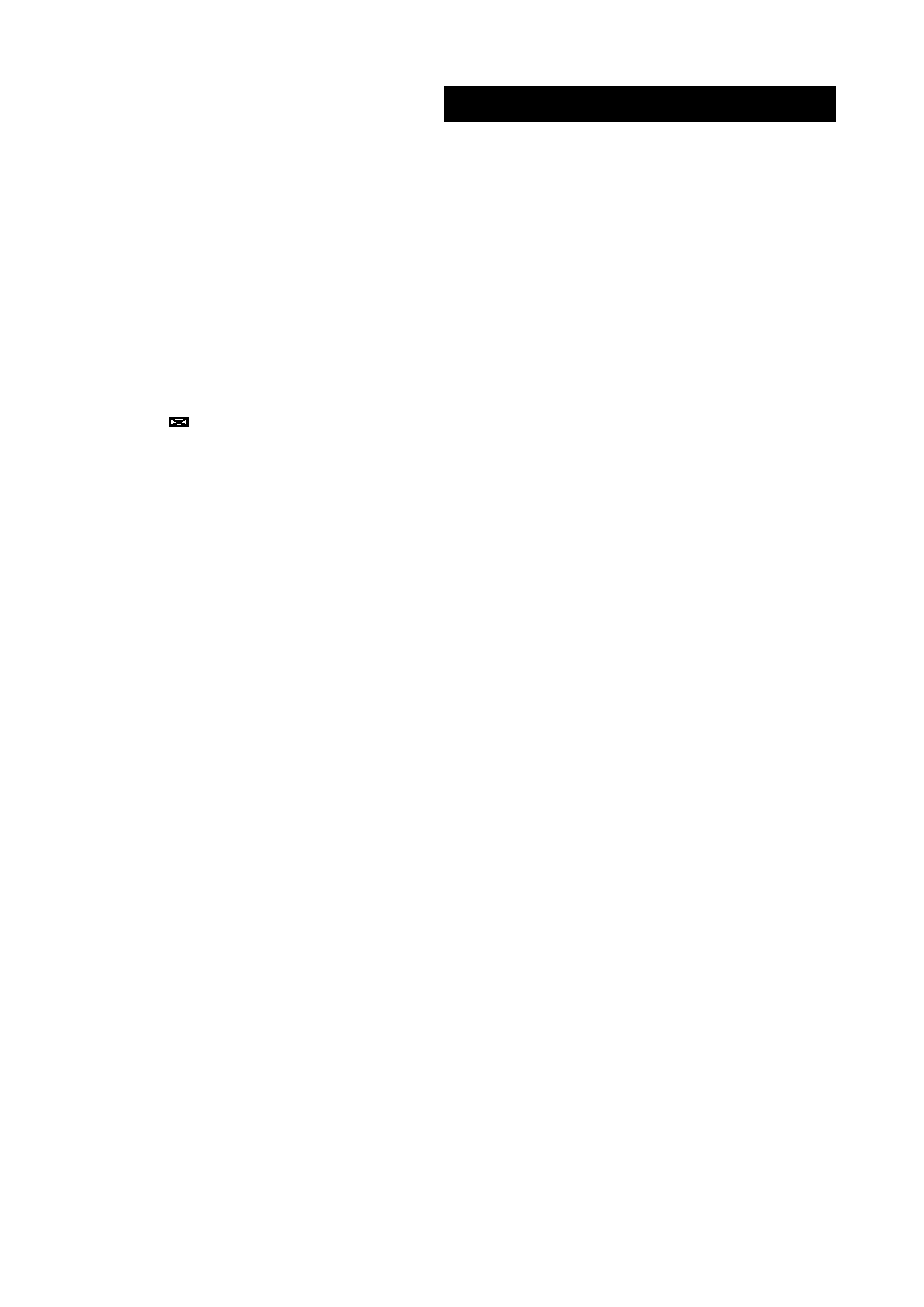

The mean BMI z score of the respondents was -0.46 (SD

cally significant (p = 0.020). Table 3

1.23) and ranged from -4.04 to +3.03 which indicates

that on the average, the study population consisted

Table 2: The

snacking pattern

(intake, daily

frequency and

the

mainly of normal weight children although there was a

type of snack taken in between meals) of the respondents

wide spectrum from severe thinness (underweight) to

Variable

Frequency (N)

Percent (%)

obese respondents. Fig 1

Intake of snacks

No

35

17.9

Fig 1: Distribution

of the

BMI for

age z-scores

of the

respon-

Yes

160

82.1

dents compared with the WHO growth reference for school

Type of snack

aged children and adolescents

None

35

17.9

Pastries*

139

71.3

Soft drinks

9

4.6

Ice

cream

6

3.1

Fruit

3

1.5

Groundnut

3

1.5

Daily frequency

None

35

17.9

1-2

129

66.2

3-4

28

14.4

≥

5

3

1.5

Purchase of sugar sweetened beverages

Often

81

41.5

Rarely

114

58.5

Total

195

100.0

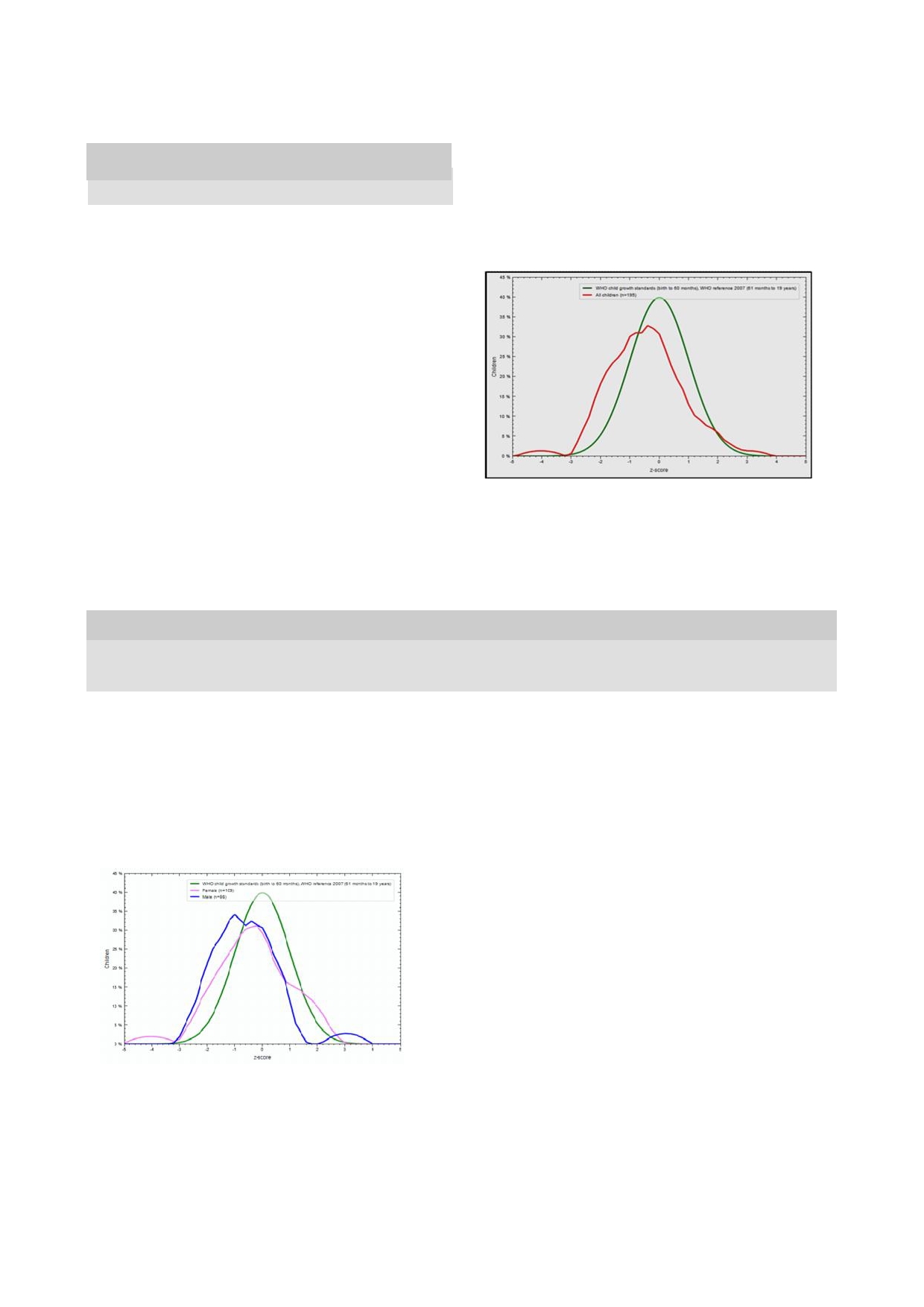

The mean BMI z score for the male respondents was -

*Pastries: Biscuits, Egg roll, Cake, Meat pie.

0.61, SD 1.13 while that for the females was -0.35, SD

1.31. Thus, both gender on the average had normal BMI.

However, the males had a greater tendency to under-

weight than the female respondents. Fig 2

Table 3: The

blood pressure,

glycaemic status

and the

BMI of

the respondents

BMI

category

Underweight

Normal

Overweight

Obese

Variable

Frequency (%)

Test statistic

Glycaemic status

Normal

23(12.0)

147

(77.0)

15

(7.8)

6

(3.2)

Fisher’s exact = 0.889

Elevated

0

(0.0)

4(100.0)

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

p = 1.000

BP status

Normal

23

(12.2)

148

(78.3)

12

(6.3)

6

(3.2)

Fisher’s exact = 8.886

Elevated

0

(0.0)

3

(50.0)

3

(50.0)

0

(0.0)

p = 0.020

Fig 2: Distribution

of the

BMI for

age z

score of

the respon-

BenueState and Ile-Ife, Osun State in Nigeria and

12

10

dents according to gender compared with the WHO growth

another study carried out in Khartoum, Sudan with

21

reference for school aged children and adolescents

reported prevalence of 9.7%, 13.7% and 14.8% respec-

tively. The observed prevalence of overweight in this

study was higher than findings reported in several stud-

ies

done in Southern Nigeria with reported prevalence of

6.7%, 5.7%, 4.1% and 1.6% in Abia, Port Har-

22

24

and Owerri respectively. The pro-

25

court, Anambra

23

portion of obesity observed in this study was akin to

findings from several studies carried out in Nigeria, such

as: 3.0% in Lagos 2.8% in Ile-Ife, and 2.3% reported

26

10

in

Calabar, but higher than 1.8% in Benue State and

11

12

Owerri including 0.8% in Abia. The value was how-

25

22

ever lower than 5.9%, 5.2% and 10.5% reported in stud-

ies done in Port Harcourt, Ile-Ife in Nigeria and Khar-

23

27

toum, Sudan respectively.

21

Discussion

The

varying values could be because of the different

study populations comprising of only school aged chil-

The

prevalence of overweight in this study was 7.7%

dren, a combination of school aged children and adoles-

which is lower than those reported in studies done in

cents up to 18 years or adolescents only. This study re-

11

cruited school aged children only. Furthermore, the

sugar sweetened beverages will increase the caloric in-

method used in defining overweight and obesity differed

take of the children and could result in weight gain

as

some of the studies used the BMI alone or BMI per-

which might predispose the respondents to overweight

and obesity and their consequences.

34

centiles. Also, different BMI percentile charts are avail-

able such as the NCHS/WHO chart of 1977 and the

The study also revealed that almost all of the respon-

2007 WHO percentile charts used in this study. It has

dents were normotensive and normoglycaemic. The rela-

been reported that these two reference charts differ sig-

tively low prevalence of elevated blood pressure and

nificantly as the 2007 WHO chart used a more diverse

blood sugar is commendable and could be a reflection of

population in the sampling and also used the growth

the low proportion of overweight and obese respondents

curve of the exclusively breast fed child as the stan-

in

this study. The proportion of respondents with high

dard. There is a need for uniformity in the assessment

27

blood pressure in this study was 3.1% which is lower

of

OWOB amongst children to allow for adequate com-

than 4.7%, 4.9%, and 5.6% reported in Port Harcourt,

Nigeria, Khartoum, Sudan and Sarvabad, Iran

23

21

35

parisons and monitoring to be done.

re-

spectively. There was no significant association between

The large proportion of normal weight school aged chil-

OWOB and elevated blood sugar amongst the study

dren when compared with the WHO child growth stan-

respondents as all of those with elevated blood sugar

dards is encouraging as it indicates that over two-thirds

had normal BMI z-score.

of

the respondents likely have optimal nutritional status.

It

however does not exclude covert micronutrient defi-

Furthermore, half of those with elevated blood pressure

ciency. In addition, over a fifth of the respondents were

were overweight and this association was statistically

malnourished if proportions of overweight, obese and

significant. In addition, 2.0% of the respondents with

underweight respondents are combined. This may indi-

normal BMI had elevated blood pressure in contrast to

cate that some of the objectives of the National School

the overweight respondents where a quarter had elevated

Health Policy such as the improvement of the nutritional

blood pressure. Obesity is known to be associated with

status of school children through provision of at least

elevated blood pressure due to the increased salt reten-

tion and hyperinsulinaemia

36,37

one adequate meal a day to school children and regular

that is linked to this con-

deworming are being poorly implemented in the study

28

dition. The finding in this study is similar to that of a

study done in Seychelles in which the obese boys and

38

area which may necessitate further studies involving the

schools in order to assess the school feeding services in

girls had three and five times higher proportion respec-

the study area.

tively of elevated blood pressure when compared to their

colleagues with normal BMI. This is important because

The findings from this study show that the twin problem

in

most cases these children are asymptomatic initially

of

underweight and OWOB was identified among the

and might only present later with end organ damage

study respondents. This is similar to what other re-

which have the potential of reducing their life expec-

searchers have reported in South Africa

29

as

well as in

tancy and quality of life.

39,40

In

order to curb this, health

25

and Anambra within

24

Uyo, Owerri,

15

Osun State,

10,30

screening for overweight and obesity amongst school

Nigeria. This shows that the ‘double - burden’ of dis-

aged

children through full implementation and strength-

ease

as described is a burgeoning problem within the

31

ening of the school health services should be done.

study locale. This is of public health significance as it is

a

reflection of the potential disease burden that the

health systems within the study area may have to grap-

ple with. This burden would therefore likely consist of

Conclusion

the more traditional problems of infectious diseases as

well as illnesses resulting from malnutrition and under-

In

conclusion, the prevalence of overweight and obesity

weight and in addition face the impact of the non-

was 7.7% and 3.1%. Also, the prevalence of hyperten-

communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension,

sion and elevated blood glucose was 3.1% and 2.1%,

diabetes and obesity that have been linked with child-

amongst school aged children and females had a higher

hood OWOB.

6,7,32

The prevalence of underweight in the

proportion of OWOB than males in Egor Local Govern-

study (11.8%) was lower than 17.0%, 17.3% and 22.7%

ment Area, Benin City, Nigeria. There is a need for pub-

reported for Owerri, Osun and Edo State in general

25

30

33

lic enlightenment towards promoting healthier lifestyle

which could possibly be because the study area is rela-

choices such as good nutrition and increased physical

tively better developed and more affluent than those

activities including screening of disease conditions early

combining rural settlements.

in

childhood. In addition, the use of fruits and nuts as

snacks should be promoted by making these readily

A

high proportion of the respondents took snacks in-

available in the homes instead of the less healthy alter-

between meals especially pastries. Few took either fruits

native of sugar sweetened beverages. This can be done

or

groundnut (legumes). The use of fruits and nuts as

by

encouraging home and/or community gardening.

snacks should be promoted and made readily available

in

the homes. Access to sugar sweetened beverages that

are

patronized by a high proportion of children, which

Conflict of Interest: None

was reported in this study should be minimized in order

Funding: None

to

reduce their consumption. Frequent consumption of

12

Acknowledgement

The

authors wish to express their gratitude to the people

of

Uselu community for the cooperation granted the

researchers during the study period.

Reference

1.

Maqbool A, Stettler N, Stallings

10.

Adegoke SA, Adeodu OO, Olowu

20.

Salman Z, Kirk GD, Deboer MD.

VA.

Nutrition. In: Kliegman RM,

WA,

Elusiyan JBE. Prevalence of

High Rate of Obesity-Associated

Stanton DF, Schur NF, Geme JN,

overweight and obesity among

Hypertension among Primary

Behrman RE editors. Nelson Text-

children in Ile-Ife. Department of

School children in Sudan. Int J

book of Paediatrics. 19 ed. Phila-

th

Paediatrics, Obafemi Awolowo

Hypertens 2011:629492.

delphia: Saunders Elseiver. 2011:

University Ile-Ife; 2009.

21.

Odenigbo UM, Nkwoala CC,

160.

(Unpublished report)

Okpala OC. Impact of birth

2.

Allison DB, Matz PE, Pietrobelli

11.

Ansa VO, Odigwe CO, Anah MU.

weight on the nutritional status

A,

Zannolli R, Faith MS. Genetic

Profile of body mass index and

and

academic performance of

and

environmental influences on

obesity in Nigerian children and

school age children. Paki

J Nutri.

obesity. In:Bendich A, Deckel-

adolescents. Niger

J Med .

2001;

2010; 9: 1157 – 1161.

baum

RJ, editors. Primary and

10: 78-80.

22.

Okoh BA, Alikor EA, Akani N.

secondary preventive nutrition.

12.

Musa DI, Toriola AL, Monyeki

Prevalence of hypertension in

Totowa NJ: Humana Press. 2001:

MA,

Lawal B. Prevalence of child-

primary school-children in Port

147-164.

hood and adolescent overweight

Harcourt, Nigeria. Paediatr

Int

3.

Federal Ministry of Health

and

obesity in Benue State, Nige-

Child Health . 2012; 32: 208 – 212 .

(Nigeria) Nutrition Division. Na-

ria. Trop

Med International

23.

Nwabueze AS, Ilika AL, Azuike

tional Policy on Infant and Young

Health. 2012; 17: 1365-1375.

EC,

Nwabueze NC, Obi KM et

Child Feeding in Nigeria.

13.

National Population Commission

al. Assessment

of nutritional

Abuja.2005.

(Nigeria). Population distribution

status among primary pupils in

4.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Inter-

by

sex, state, LGAs and senatorial

rural and urban areas of Anambra

national Obesity Task

districts: 2006 Census priority

State. Euro

J Preventive

Med,

Force: Obesity in children and

Table IV. Vol 3. Accessed May

2015;3(2): 34-38 doi: 10.11648/

young people: a crisis in public

2014. Available from

j.ejpm.20150302.14

health. Obes

Rev 2004;

1: 4-104.

www.population.gov.ng/.

24.

Nnebue CC, Ilika AI, Uwakwe

5.

St

Onge M P, Keller K L, Heyms-

14.

Cochran WG. Sampling Tech-

KA,

Duru CB, Onah SK et

al.

field S B. Changes in childhood

niques, 2nd Ed.,New York: John

Feeding practices and determi-

food consumption patterns: a cause

Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1963

nants of the nutritional status of

for

concern in light of increasing

15.

Opara DC, Ikpeme EE, Ekanem

pupils in a public primary school

body weights. Am

J Clin

Nutr

US.

Prevalence of stunting, under-

in

Aladinma Owerri, Nigeria. Intl

2003;78:1068 – 1073.

weight and obesity in school aged

J. Clin Nutrition, 2016; 4(1): 12-

6.

WHO. Prioritizing areas for action

children in Uyo, Nigeria .

Pak. J

18 doi: 10.12691/ijcn-4-1-3

in

the field of population-based

Nutr . 2010; 9:459-466.

25.

Ben-Bassey UP, Oduwole AO,

prevention of childhood obesity: a

16.

Han ST, Sattar N, Lean M. Assess-

Ogundipe OO. Prevalence of

set

of tools for Member States to

ment

of obesity and it’s clinical

overweight and obesity in Eti-Osa

determine and identify priority

correlation. BMJ.

2006; 333:

695-

LGA, Lagos, Nigeria. Obes

Rev.

areas for action. Accessed January

698.

2007; 8:457-459.

2015. Available from

17.

Timmis A. Cardiovascular System.

26.

Sabageh AO, Ojofeitimi EO.

www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/

In:

Sawash M, Glynn M eds. Hut-

Prevalence of obesity among

childhood/Childhood_obesity.

chinson’s Clinical Methods, an

adolescents in Ile- Ife, Osun

7.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW,

integrated approach to clinical

State, Nigeria using body mass

van

Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ.

practice. Sunders Elseiver: USA.

index and waist hip ratio: a com-

Tracking of childhood overweight

2007:77.

parative study. Niger

Med J.

into adulthood: a systematic re-

18.

Olusanya O, Okpere E, Ezimokhai

2013; 54: 153-156.

view of the literature. Obes Rev .

M.

The importance of social class

27.

Federal Ministry of Education

2008; 9: 474-88.

in

voluntary fertility control in a

(Nigeria). National School Health

8.

World Health Organization. Popu-

developing country. West

Afr J

Policy. Abuja, 2006. Accessed

lation-based prevention strategies

Med . 1985;4:205-212.

May

2015. Available from

for

childhood obesity: report of a

19.

WHO. Growth reference data for 5

www.unicef.org/nigeria/

WHO

forum and technical meet-

-19

years. Accessed June 2014.

school_health_policy.pdf.

ing, Geneva, 15 – 17 December

Available from www.who.int/

28.

Toriola AL, Moselakgnmo VK,

2009.Geneva: World

Health

growthref/en/ National Institute for

Shaw BS Goon DT. Overweight,

Organization; 2010.

Health (USA). Blood pressure

obesity and underweight in rural

9.

World Health Organization. Obe-

levels for boys and girls by age and

black South African children. S

sity: Preventing and Managing the

height percentile. Accessed June

Afr J Clin Nutr . 2012; 25: 57- 61 .

Global Epidemic. World Health

2014. Available from

Organization Technical Support

www.nhlbi.nih.gov

Series 894: World Health Organi-

zation Geneva, Switzerland. 2000

13

29.

Adeomi AA, Adeoye OA,

33.

Ansa VO, Anah MU, Ndifon WO.

36.

Chiolero A, Gray M, Anderson

Bamidele JO, Abodunrin OL, Odu

Soft drink consumption and over-

G,

Burnier M, Paccaud F et al.

OO,

Adeomi OA. Pattern and de-

weight/obesityamong Nigerian

Prevalence of elevated blood

terminants of the weight status of

adolescents. CVD

Prevention

pressure and association with

school-age children from rural and

Control, 2008: 3: 191-196

overweight in children of a rap-

urban communities in Osun State,

34.

Rezaeian S, Ahmadzadeh J, Es-

idly developing country. J

Human

Nigeria: a comparative study. J

mailnasab N, Veisani Y, Shayan

Hyperten . 2007; 21:120-127.

Med Nutr Nutraceuticals, 2015; 4

M,

Moradi N. Assessment of

37.

Scott IU, Siatkowski RM, Eneyin

(2):107-114

Health and Nutritional Status in

NM,

Brodsky MC, Lam BL. Idio-

30.

Theobald NS, Suchindran C, North

Children Based on School Screen-

pathic intracranial hypertension in

KE,

Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P.

ing

Programs. Health

Scope, 2014;

children and adolescents. Am J

Association of adolescent obesity

3(1): e14462 doi: 10.17795/

Opth . 1997; 124: 253-255.

with risk of severe obesity in adult-

healthscope-14462

38.

Lindhal BI, Jihansson LA. Multi-

hood. JAMA .

2010; 304(18):2042-

35.

WHO. Prioritizing areas for action

ple

cause-of death data as a tool

7.

in

the field of population-based

for

detecting critricial trends in

31.

Gunnell DJ, Frankel SJ, Nanchahal

prevention of childhood obesity: a

the

underlying cause statistics: a

K,

Peters TJ, Snith GD. Childhood

set

of tools for Member States to

methodological study. Scand

J

obesity and adult cardiovascular

determine and identify priority

Soc Med . 1994; 22: 145-158.

mortality: a 57 year follow up

areas for action. Accessed January

39.

Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler

study based on the Boyd Orr co-

2015. Avaliable from

WC,

Sievers ML, Bennett PH et

hort. Am

J Clin

Nutr , 1998;

67(6):

www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/

al.

Childhood obesity, other car-

1111- 1118.

childhood/Childhood_obesity.

diovascular risk factors and pre-

32.

Edo State Ministry of Health. Edo

mature death. N

Engl J

Med .

State Government 2010-2020 Stra-

2010; 362:485-493

tegic Plan: Edo State Basic health

and

social data. 2009; 1- 121.