Copyright 2015 © Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. All Rights Reserved. . Powered by Pelrox Technologies Ltd

ISSN 03 02 4660 AN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA

Quick Navigation

Niger J Paediatr 2016; 43 (4): 273 – 280

ORIGINAL

Kuti BP

Prevalence and predictors of

Adetola HH

Aladekomo TA

hypoxaemia in hospitalised

Kuti DK

children at the emergency unit of

a resource constrained centre

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i4.8

Accepted: 23rd August 2016

Abstract :

Background: Hypoxae-

features. Eighty three (20.6%)

mia is often poorly detected and

were hypoxaemic including 40

Kuti BP (

)

treated in emergently-ill children

(38.1%) of those with respiratory

Aladekomo TA

in

resource-poor centres because

features at admission. Infancy,

Department of Paediatrics and

of

the non-availability of pulse

chest in-drawing, cyanosis and

Child Health

oximeters and similar facilities to

grunting were associated with hy-

Obafemi Awolowo University,

detect it. This study sets out to

poxaemia (p < 0.05) among those

Ile-Ife, Nigeria

determine the prevalence and sim-

with respiratory features, while

Email: kutitherapy@yahoo.com

ple predictors of hypoxaemia

infancy, pallor and tachycardia

among children with or without

were significant among those with

Adetola HH, Kuti DK

respiratory features at the emer-

no

respiratory features. Grunting

Department of Paediatrics,

gency unit of the Wesley Guild

(OR = 7.875; 95% CI=1.029-

Wesley Guild Hospital, Ilesa,

Hospital, Ilesa, Nigeria

15.797; p = 0.045) and Cyanosis

Nigeria

Methods:

Children aged one

(OR =13.579; 95% CI = 1.360-

month to 14 years were consecu-

14.379; p = 0.009) independently

tively recruited and prospectively

predict hypoxaemia among the

studied over an eight month pe-

children with respiratory features.

riod. All the children had their

Conclusion: Hypoxaemia

occurred

peripheral

oxygen

saturation

in

approximately one out of five ill

(SpO 2 ) measured at

presentation

children admitted to the emer-

using a portable pulse oximeter

gency unit of the WGH, Ilesa and

(Nellcor

(R)

N-200, USA) and hy-

was significantly associated with

poxaemia was defined as SpO 2

<

mortality. Emergently ill children

90%. Relevant history and exami-

with

cyanosis and grunting espe-

nation findings were compared

cially infants should preferentially

among hypoxaemic and non-

be

placed on oxygen therapy even

hypoxaemic children. Multivari-

when hypoxaemia cannot be con-

ate

analysis was used to predict

firmed.

the

presence of hypoxaemia.

Results: Four

hundred and

two

Key words :

Emergently ill

chil-

children were recruited with male

dren, hypoxaemia, predictors, re-

to

female ratio of 1.3:1 and105

source-poor.

(26.1) presented with respiratory

Introduction

The burden of hypoxaemia in developing countries is

huge because a large proportion of children are brought

Hypoxaemia has been recognised as a sign of serious ill-

into the hospital in serious condition requiring emer-

gency care. Subhi and his group in a systematic re-

5

6

health in children because it often denotes poor ventila-

tion and or perfusion and an urgent need for oxygen

view estimated that 13% (1.5 - 2.7 million) children

therapy.

1-2

Oxygen supply in busy emergency units of

with pneumonia in developing countries who presented

to

health facilities annually are hypoxaemic. Emordi

et

6

resource constrained developing countries is not always

al also

reported that

13% of

children aged

2 to

59

7

available and or affordable. Sometimes oxygen supply

3

is

rationed among children who need it because de-

months admitted to the children emergency unit of a

mands often outweigh supply.

3-4

Ill children are often

tertiary centre in South East Nigeria were hypoxaemic.

7

not well screened for need for oxygen therapy because

Orimadegun et

al however reported a much higher

8

of

the non-availability of pulse oximeters and similar

prevalence of 28.6% among emergently ill neonates and

facilities. These often lead to denial of oxygen therapy

4

children at another tertiary facility in Nigeria and a

to

children whose survival depends on this life-saving

much higher prevalence of 49.2% among those with

respiratory tract infections. Other studies from develop-

8

therapy.

3-4

274

ing

countries including the west African sub region also

Subject recruitment

reported a huge burden of hypoxaemia among ill chil-

dren.

9-12

Unfortunately oxygen supply to meet this huge

Consecutive admissions into the CEW whose parents/

demand is not always available in most of the centres .

3-

caregivers gave consent were recruited for the study.

4

A

large proportion of emergently ill children in devel-

Children admitted with all forms of shock were ex-

oping countries particularly those with non-respiratory

cluded because their peripheral oxygen saturation

symptoms may however remain unrecognised and thus

(SPO 2 ) could not be measured

with pulse oximetry due

to

systemic hypo perfusion.

15

untreated as most reported studies on hypoxaemia

The (SPO 2 ) of the re-

among ill children were done on those with respiratory

cruited children were recorded using a portable pulse

symptoms at presentation.

6

oximeter (Nellcor N-200, USA) by a study assistant who

did

not take part in the history taking and subsequent

Many

centres in resource – poor countries still adminis-

management

of the patients. The SPO 2 was

taken using

ter

oxygen to emergently ill children without diagnosing

an

appropriately sized paediatric probe attached to the

hypoxaemiaobjectively.

3-4

This is often due to non-

finger or toes for at least 30 seconds till the reading of

availability of pulse oximeters and other facilities to

the oximeter is stabilised. Hypoxaemia which is the out-

make this diagnosis.

3-4

This brings to the fore a need for

come variable was defined in this study as SPO

2 < 90%.

2,

simple, easily measureable parameters that could guide

5

clinicians in resource-poor centres in prompt recognition

The study variables included age of the patients, sex,

of

hypoxaemia in emergently ill children with or without

and parental socioeconomic class derived using rank

respiratory symptoms to improve survival. This study

assessment of the parents’ highest level of educational

therefore sets out to determine the prevalence and pre-

attainment

and

occupation

as

described

by

Oyedeji. Also of interest were the clinical features at

16

dictors of hypoxaemia among emergently ill children at

the Wesley Guild Hospital (WGH), Ilesa, Nigeria.

presentation including axillary temperature taken using a

low reading clinical thermometer. Hypothermia was

recorded as temperature less than 35 C; subnormal as 35

0

–

36.5 C; normal as 36.5 to 37.5 C; fever as 37.5 to

0

0

Patients and Methods

38.5 C, and hyperpyrexia as >38.5 C.

0

0

5,17

Other features

at

presentation considered included convulsion, diar-

This was a prospective cross sectional study of children

rhoea, cyanosis, pallor and prostration. The study par-

aged 1 month to 14 years admitted over an eight month

ticipants were categorised into those with respiratory

period (January to August, 2015) at the Children Emer-

features and those without respiratory features at presen-

gency Ward (CEW) of the WGH, Ilesa, Nigeria. The

tation. The respiratory features looked for in these chil-

WGH is a tertiary annexe of the Obafemi Awolowo Uni-

dren included fast breathing defined using the WHO cut

versity Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC),

off thus (respiratory rate >50 cycles per minute in chil-

Ile‑ Ife. The hospital is one of the main

referral centers

dren less than 12 months; > 40cpm in children 1-5 years

providing specialized pediatric care for the communities

and > 30cpm in those > 5 years); noisy breathing includ-

of

Osun, Ondo, and Ekiti States of the South‑ West Ni-

ing

grunting, wheezing and stridor, nasal flaring and

chest in-drawing. Tachycardia was defined as pulse

17

geria. The children emergency ward of the hospital oper-

ates a 24‑ h service and admits about

600 children per

rate> 150 beats per minute in children 1-3 years and >

140 beats per minute for children > 3 years. The nutri-

17

annum. The hospital has functional biochemical, micro-

biological and hematological laboratory services as well

tional status of the children was assessed using Well-

come classification.

18

as

well‑ equipped and staffed radiological

services

The

children were investigated

which also operate on a 24 h basis.

appropriately based on the presentation. Diagnoses was

Ilesa, the largest town in Ijesaland is situated on latitude

made

based on the unit standard protocol and these were

7°35’N and longitude 4°51’E and is about 200 km

in

line with the WHO guidelines for the management of

common childhood illnesses.

17

North‑ East of Lagos a major commercial

nerve center

The outcomes of hospi-

of

Nigeria. Ilesa is home to about 620,000 people with

13

talisation were recorded as discharged home, died, dis-

about 25% of the population being children <5 years and

charged against medical advice (DAMA) and referred to

up

to 40% children <15 years. The people in Ilesa

13

another health facility.

called Ijesa are mainly traders, peasant farmers, artisans,

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the

and civil servants.

13

Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi

Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex

Study size

(OAUTHC), Ile-Ife, Nigeria with protocol number

ERC/2014/08/05. Informed consent and assent (as ap-

The minimum sample size for this study was estimated

propriate) were also obtained from the study partici-

14

using Fisher’s formula.

With reference 49.2% preva-

pants.

lence of hypoxaemia among emergently ill children

from a previous study, a minimum total of 384 study

8

Data analysis

participants was estimated. Adding attrition rate of about

five percent, total of 402 children were recruited for the

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows software

study

version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago 2008). Differences

between the means (SD) or median (IQR) values of con-

275

tinuous variables were determined using Student’s t‑

test

Results

or

Mann – Whitney U‑ test; while the

differences between

proportions of categorical variables were determined

Over

an eight month study period, a total of 424 chil-

using Pearson’s Chi‑ squared or

Fisher’s exact tests. The

dren were admitted to the CEW, 22 children were ex-

level of significance at a 95% confidence interval was

cluded including 19 who presented with shock and 3

set at P <0.05. Associations between the presence or

children whose parents did not consent to participate in

absence of hypoxaemia and the study variables that gave

the

study. A total of 402 children were recruited for the

significant results were further analyzed with binary

study and form the basis of further analysis. 105

logistic regression to determine the independent predic-

(26.1%) of the children had respiratory features at pres-

tors

of hypoxaemia among the children with or without

entation. Eighty three (20.6%) of the children were hy-

respiratory features at presentation. Results were inter-

poxaemic at presentation, this included 40 (38.1%) of

preted with Odds ratios (OR) and 95 percent confidence

the

105 children with respiratory features and 43

interval (CI). Statistical significance was established

(14.5%) of 297 with no respiratory features at presenta-

when

CI does not embrace unity.

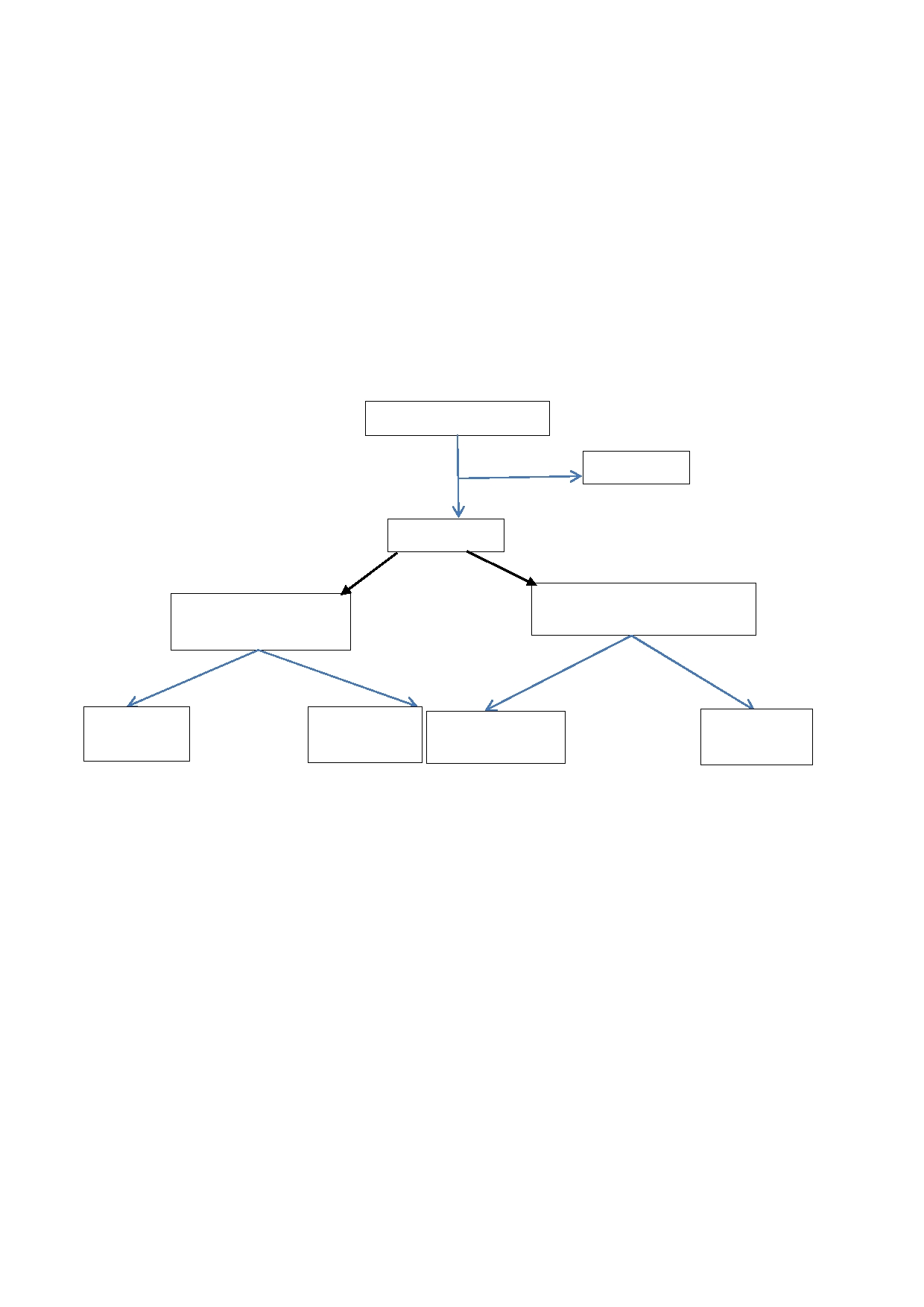

tion. Figure 1 highlights the study participants and

subgroups in a flow chart.

Fig 1: Flow

chart of

the recruitment

of the

study participants

424 children admitted

22

excluded

402 recruited

297 without respiratory features

105 with respiratory

at

presentation

features at presentation

40

were hy-

65

were non-

43

were hypoxae-

254 were non

poxaemic

hypoxaemic

mic

-hypoxaemic

Socio-demographic and general characteristics of the

grunting respiration 12 (11.4); wheezing 10 (9.5%); na-

study participants

sal flaring 50 (47.6%)and chest in-drawing 42 (40.0)

were more commonly observed. Table 2 highlights the

Age and Sex: The

ages of

the children

ranged from

one

clinical presentation of the emergently ill children with

to

168 months with a median interquartile (IQR) age of

or

without respiratory features at presentation. Majority

24

(15 - 42) months. Majority (72.1%) of the children

(82.3%) of the children had normal nutritional status.

were under-fives including 84 (20.8%) infants. Of the

The spectrum of malnutrition observed in the children is

402 study participants, 226 (56.2%) were males with a

also highlighted in table 2.

male to female ratio of 1.3:1.Table one highlights the

The duration of illness before presentation in the 402

socio-demographic characteristics of the study partici-

recruited children ranged from one to 28 days with a

pants as related to the presence or absence of respiratory

median (IQR) of 2 (1-3) days. No significant difference

features at presentation.

in

the Median (IQR) duration of illness before presenta-

Parental socio-economic class:

Majority (77.4%)

of the

tion between the children with respiratory features and

emergently ill children were from middle social class,

those without respiratory features. (Mann Whitney U

while only 31 (7.7%) were from upper social class.

=14973.500; p = 0.716) Majority (74.9%) of the

children presented within three days of illness.

Clinical features at presentation

Fever was the most prominent feature at presentation

reported in 352 (87.6%) of the children. Others present-

ing features included convulsions 152 (37.8%) pallor

138 (34.3%), cough (19.2), vomiting 48 (11.9%) and

loss of consciousness 52 (12.9%).Among the 105 chil-

dren with respiratory features, tachypnoea 90 (85.7%);

276

Table 1: Socio-demographic

and general

characteristics of

the

Factors associated with hypoxaemia among the children

study

participants as related to the presence or absence of res-

piratory symptoms at presentation

Among the children with respiratory features: Infancy

Socio-demographic

Children with

Children with

Total

was significantly associated with the presence of hypox-

features

respiratory

no

respiratory

n =

402

aemia, as 21 (55.3%) of the 38 infants with respiratory

symptoms

features

features compared to 19 (28.4%) of 67 children> one

n =

105 (%)

n=

297 (%)

year were hypoxaemic at presentation (x = 7.443; p <

2

Age range (in years)

0.006). Table III. Conversely, older children (> one

< 1 (infants)

38

(36.1)

46

(15.5)

84

year) were less likely to be hypoxaemic at presentation.

1

-5

55

(52.4)

191

(64.3)

246

The presence of chest in-drawing (52.4% vs. 31.7%;x =

2

6-

14

12

(11.4)

60

(20.2)

72

6.058; p = 0.014), grunting respiration (80.0% vs.

Sex

58.2%; x = 8.148; p = 0.004) and Cyanosis (87.5% vs.

2

Male

63

(63.9)

163

(54.2)

226

57.9%; x = 9.135; p = 0.003) were significantly associ-

2

Female

42

(36.1)

134

(45.8)

176

ated with hypoxaemia among emergently ill children

Parental social class

with respiratory features at presentation. (Table 3)

Upper

class

2

(2.4)

29

(9.1)

31

Among the children with no respiratory features at pres-

Middle class

65

(78.3)

246

(77.1)

311

entation: Infancy was also significantly associated with

Lower class

16

(19.3)

42

(13.2)

58

hypoxaemia among the emergently ill children with no

Place of residence

respiratory features at presentation (x = 5.924; p =

2

Within Ilesa

70

(66.7)

120

(40.4)

190

0.015). Also, pallor (20.6% vs. 14.5%; x = 4.684; p =

2

Outside Ilesa

35

(33.3)

177

(59.6)

212

0.030) and tachycardia (27.3% vs. 14.8%; x = 6.829; p

2

=

0.009) at presentation were significantly associated

The

figures in parentheses are percentages of the total in each

column

with hypoxaemia among the children. (Table 3)

Nutritional status and the presence of hypoxaemia at

Table 2: Clinical

features at

presentation as

related to

the

presence or absence of respiratory features

presentation

Clinical

features at Children with Children with Total

No

significant association was observed between the

presentation

respiratory

no

respira-

n =

402

nutritional status of the children and the presence of

features

tory

features

hypoxaemia at presentation. Table 4 highlights the nu-

n =

105

n =

297

Temp at admission

tritional status of the children with or without respiratory

Hypothermia

1

(1.0)

4

(1.4)

5

features and the presence of hypoxaemia at presentation.

Subnormal

6

(5.7)

11

(3.7)

17

Normal

7

(6.7)

12

(4.0)

19

Outcome of hospitalisation as related to hypoxaemia at

Fever

84

(80.0)

268

(90.2)

352

presentation

Hyperpyrexia

7

(6.7)

2

(0.7)

9

Clinical features

Outcome of hospitalisation:

Majority (93.0%)

of the

DOI median

(IQR)

2.0 (1.0 –

4.0) 3.0 (1.0 – 3.0)

children were discharged home, while 13 (3.2%) of the

Convulsion

20

(19.1)

135

(45.5)

155

children died. (Table 4). The duration of hospitalisation

Pallor

36

(34.3)

102

(34.3)

138

ranged from few hours to 33 days with a median (IQR)

Cough

98

(93.3)

57

(19.2)

77

duration of 3.0 (2.0 – 4.0) days.

Tachycardia

31

(29.5)

44

(14.8)

75

Length of hospitalisation:

Emergently ill

children with

Diarrhoea

4

(3.8)

12

(4.0)

16

hypoxaemia at presentation significantly stayed longer

Coma

2

(1.9)

50

(16.8)

52

in

the hospital compared to non-hypoxaemic children.

Vomiting

10

(9.5)

38

(12.8)

48

(Median (IQR) 4.0 (2.0 – 6.0) days vs. 3.0 (2.0 – 4.0)

Dehydration

5

(4.8)

17

(5.7)

22

days, Mann Whitney U = 9.911, p < 0.001).

Prostration

2

(1.9)

23

(7.7)

25

Mortality: Significantly

more emergently

ill children

Tachypnoea

90

(85.7)

0

(0.0)

100

with hypoxaemia at presentation compared to non-

Nasal

flaring

50

(47.6)

0

(0.0)

50

hypoxaemic children died as 8 (9.6%) of the 83 hypox-

Chest

in-drawing

42

(40.0)

0

(0.0)

42

aemic children compared to 5 (1.5%)of the 329 non-

Stridor

6

(5.7)

0

(0.0)

6

hypoxaemic children, died. The association between

Grunting

12

(11.4)

0

(0.0)

12

Cyanosis

6

(5.7)

2

(0.6)

8

hypoxaemia and mortality is significant irrespective of

Wheezing

10

(9.5)

0

(0.0)

10

the

presence or absence of respiratory symptoms at pres-

Nutritional status

entation as highlighted in table 5.

Normal

80

(76.2)

251

(85.6)

331

Underweight

17

(16.2)

33

(11.9)

50

Predictors of hypoxaemia among emergently ill children

Marasmus

5

(4.8)

10

(2.8)

15

Kwashiorkor

0

(0.0)

1

(0.0)

1

The variables found to be significantly associated with

Overweight/Obese 3 (2.9)

2

(0.9)

5

hypoxaemia among the emergently ill children with or

without respiratory features at presentation (tables 3 and

The figures

in parentheses are percentages of the total in

4)

were further subjected to binary logistic regression

each column.

Temp = temperature; DOI = Duration of ill-

ness before

presentation; IQR = interquartile range

analysis to determine the independent predictors of

277

hypoxaemia. Grunting respiration (OR = 7.875; 95%CI

ergently ill children with respiratory features at the

=

1.029 – 15.797; p = 0.045) and Cyanosis at presenta-

WGH,

Ilesa. However, among the children with no res-

tion

(OR = 13.576; 95%CI 1.360 – 14.279; p = 0.009)

piratory features, none of the variables independently

were independent predictors of hypoxaemia among em-

predict hypoxaemia (Table 6)

Table 3: Socio-demographic

characteristics and

clinical features

of the

children as

related to

the presence

of hypoxaemia

at

presentation

Variables

Children with respiratory features n =

p-value

Children with no respiratory

p

-value

105

features n = 297

Hypoxaemic

Non-hypoxaemic

Hypoxaemic

Non-hypoxaemic

n =

40 (%)

n =

65 (%)

n =

43 (%)

n =

254 (%)

Sex

Male

26

(65.0)

37

(56.9)

0.412

27

(62.8)

136

(53.5)

0.260

Female

14

(35.0)

28

(43.1)

16

(37.2)

118

(46.5)

Age range (years)

< 1

21

(52.5)

17

(26.2)

0.006

12

(27.9)

34

(13.4)

0.015

1 -

5

15

(37.5)

40

(61.5)

<0.001

24

(55.8)

167

(65.7)

0.209

6-

14

4

(10.0)

8

(12.3)

0.716*

7

(16.3)

53

(20.9)

0.479

Social class

Upper

class

1

(2.5)

6

(9.2)

0.151*

1

(2.3)

23

(9.1)

0.087*

Middle class

32

(80.0)

53

(81.5)

0.845

33

(76.7)

195

(76.8)

0.997

Lower class

7

(17.5)

6

(9.2)

0.212

9

(20.9)

36

(14.2)

0.253

Place of residence

Within Ilesa

24

(60.0)

31

(47.7)

0.219

21

(48.8)

133

(52.4)

0.669

Outside Ilesa

16

(40.0)

34

(52.3)

22

(51.2)

121

(47.6)

Clinical features

Temperature

Hypothermia

0

(0.0)

1

(1.5)

0.326*

1

(2.3)

3

(1.2)

0.578*

Subnormal

2

(5.0)

4

(6.2)

0.803*

1

(2.3)

10

(3.9)

0.583*

Normal

2

(5.0)

5

(7.7)

0.584*

3

(7.0)

9

(3.5)

0.327*

Fever

33

(75.0)

51

(86.2)

0.615

38

(88.4)

230

(90.6)

0.656

Hyperpyrexia

3

(7.5)

4

(4.6)

0.790*

0

(0.0)

2

(0.8)

0.428

Other features

Convulsion

4

(10.0)

16

(24.6)

0.064*

14

(32.6)

111

(45.7)

0.171

Pallor

12

(30.0)

24

(36.9)

0.468

21

(48.8)

81

(31.8)

0.030

Tachycardia

13

(32.5)

18

(27.7)

0.600

12

(27.9)

32

(12.6)

0.009

Diarrhoea

3

(7.5)

10

(15.4)

0.219*

4

(1.6)

14

(5.5)

0.363*

Coma

2

(5.0)

3

(4.6)

0.929*

2

(4.7)

13

(5.1)

0.896*

Vomiting

5

(12.5)

12

(18.5)

0.242

8

(18.6)

57

(22.4)

0.574

Dehydration

3

(7.5)

2

(3.1)

0.412*

3

(7.0)

14

(5.5)

0.710*

Prostration

1

(2.5)

1

(1.5)

0.730*

1

(2.3)

22

(8.7)

0.102*

Nasal flaring

20

(50.0)

30

(46.2)

0.702

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

Chest in-

22

(55.0)

20

(30.7)

0.014

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

drawing

Tachypnoea

32

(80.0)

58

(89.2)

0.189

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

Stridor

2

(5.0)

4

(6.2)

0.803*

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

Grunting

8

(20.0)

2

(3.1)

0.004*

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

Wheezing

4

(10.0)

4

(6.2)

0.477*

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

Cyanosis

7

(17.5)

1

(1.5)

0.003*

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

The

figures in parentheses are percentages of the total in each column.* Fisher’s

exact test applied. NA = not applicable

Table 4: Nutritional

status of

the study

participants in

relation to

the presence

of hypoxaemia

at presentation

Variables

Children with respiratory features n

p-value

Children with no respiratory features n

p

-value

=

105

=297

Hypoxaemic

Non-hypoxaemic

Hypoxaemic n =

Non-hypoxaemic n

n =

40 (%)

n =

65 (%)

43

(%)

=

254 (%)

Normal

32

(80.0)

48

(73.8)

0.472

36

(83.7)

219

(86.2)

0.664

Underweight

5

(12.5)

12

(18.5)

0.421

4

(9.3)

29

(11.4)

0.737

Marasmus

2

(5.0)

3

(4.6)

0.929

1

(2.3)

5

(2.0)

0.891

Kwashiorkor

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

1

(2.3)

0

(0.0)

0.401

Overweight/Obese

1

(2.5)

2

(3.1)

0.663

1

(2.3)

1

(0.4)

0.245

The

figures in parentheses are percentages of the total in each column.* Fisher’s

exact test applied

278

Table 5: Outcome

of hospitalisation

as related

to the

presence of

hypoxaemia at

presentation

Outcome

Children with respiratory features n = 105

p-value

Children with no respiratory features n = 297

p

-value

Hypoxaemic n =

Non-hypoxaemic

Hypoxaemic n = 43

Non-hypoxaemic n =

40

(%)

n =

65 (%)

(%)

254

(%)

Discharged

36

(90.0)

61

(93.8)

0.473

38

(88.4)

239

(94.1)

0.101

DAMA

0

(0.0)

2

(3.1)

0.163*

1

(2.3)

10

(3.9)

0.583*

Died

4

(10.0)

1

(1.5)

0.049*

4

(9.3)

2

(1.2)

0.003*

Referred

0

(0.0)

0

(0.0)

NA

0

(0.0)

1

(0.4)

0.576*

The

figures in parentheses are percentages of the total in each column; DAMA =

discharged against medical advice. * Fisher’s

exact test applied

Table 6: Predictors

of hypoxaemia

among emergently

ill children

with or

without respiratory

features at

presentation using

multiple regression analysis

Variables

Coefficient of

Standard

Odds ratio

95%

confident interval

P value

regression

error

Respiratory features

Infancy

0.801

0.495

3.121

0.845 - 5.871

0.105

Grunting respiration

1.394

0.697

7.875

1.029 - 15.797

0.045

Cyanosis

1.211

0.461

13.576

1.360 - 14.279

0.009

Chest in-drawing

0.955

0.476

2.750

0.768 - 4.778

0.098

No respiratory features

Infancy

0.741

0.613

2.179

0.631 - 6.971

0.227

Pallor

1.059

0.560

2.360

0.146 - 7.167

0.054

Tachycardia

0.136

0.610

2.973

0.347 - 3.787

0.824

Diagnostic accuracy of predictors

: Grunting

respira-

inspiring against a partially closed glottis. It is a form of

2

tion among children with respiratory features has a sen-

positive pressure ventilation employed by ill children to

sitivity of 20.0%; specificity of 96.9%; positive and

overcome ventilation perfusion mismatch caused by

negative predictive values of 44.4% and 66.3% respec-

conditions that can result in increased lung dead space.

2

tively. Cyanosis among children with respiratory fea-

Inability of the compensatory mechanisms like grunting

tures has a sensitivity of 17.5%, specificity of 98.5%,

and use of accessory respiratory muscles to improve

positive and negative predictive values of 87.5% and

oxygenation often results in the build-up of deoxygen-

ated haemoglobin in the circulation. This often mani-

2

66.0% respectively.

fests clinically as cyanosis hence grunting respiration

and cyanosis are important predictors of hypoxaemia in

sick children with high specificity. However the absence

Discussion

of

grunting and cyanosis in sick children does not

exclude hypoxaemia as their sensitivity to detect hypox-

This

study has highlighted the prevalence and simple

aemia is low as observed in this study.

measurable predictors of hypoxaemia among ill children

at

the emergency unit of a resource poor centre. The

Sick Infants were observed in this study to be at in-

20.6% prevalence of hypoxaemia reported in this study

creased risk of having hypoxaemia compared to older

is

similar to reported prevalence of 19.0% in the Gambia

children. These findings were corroborated by studies

9-12

within and outside Nigeria.

8

by

Junge et

al using the same criteria. This is however,

19

This may be due to the

much higher than 13.3% reported by Emodi

et al from a

7

fact that infants have low tidal volume and relative inef-

tertiary centre in Nigeria. This difference between the

ficient compensatory mechanisms (like use of accessory

prevalence of hypoxaemia in this study compared to that

respiration muscles) to improve ventilation. In situations

of

Emodi et

al may be explaint by relative smaller sam-

7

of

increased dead space and ventilation perfusion mis-

ple size (92 children) studied by the latter compared to

match, infants are poorly equipped to compensate for

this, thus they easily succumb to hypoxaemia. Conse-

2-3

402 children recruited in this study. The prevalence of

20.6% observed in this study is much less than 52.0%

quently, ill infants should particularly be carefully as-

reported by Dukes et

al in Papua New Guinea. The

1 9

sessed for hypoxaemia at presentation and promptly

higher prevalence reported from Papua New Guinea

treated to ensure survival.

may be due to fact that it is located in a high altitude

region (1600m above sea level) with expected relative

In

addition to infancy, pallorand tachycardia were also

ambient hypoxia compared to the present study which

observed to be associated with hypoxaemia among the

was conducted at sea level.

children with no respiratory features at presentation.

This observation was corroborated by Emordi

et al who

7

Cyanosis and grunting respiration were observed to pre-

reported higher frequency of anaemia among hypoxae-

dict hypoxaemia among children with respiratory fea-

mic children in Enugu, Nigeria. Severe anaemia is the

tures in this study. This is similar to reported observa-

most common cause of pallor among emergently ill chil-

dren in malaria endemic region like our study site. Se-

5

tions in other studies in developing countries among

children with pneumonia and respiratory tract infec-

verely anaemic children may often be hypoxaemic due

tions

9-12

Grunting is an inspiratory sound produced by

to

inability of the depleted haemoglobin to carry enough

279

oxygen to meet the tissue requirements. (Anaemic hy-

ratory features at presentation and one in every seven

poxia)

2

Anaemic heart failure can also ensue in these

children with no respiratory features at presentation in

children leading to pulmonary congestion and poor ven-

Ilesa, Nigeria. The presence of hypoxaemia was signifi-

tilation and perfusion. This explains why tachycardia

2

cantly associated with mortality irrespective of the pre-

and pallor were significantly associated with the pres-

senting features. Emergently ill children in resource-

ence of hypoxaemia among the emergently ill children.

poor settings who presented with respiratory features

Hypoxaemia was observed in this study to be associated

and cyanosis, grunting respiration and chest in-drawing

with mortality irrespective of the presenting features.

and those with no respiratory features but presented with

This finding was also reported by other researchers in

pallor and tachycardia especially infants should prefer-

children with or without respiratory symptoms.

7-12, 19-20

entially be placed on oxygen therapy even when hypox-

Hypoxaemia often connote poor tissue oxygenation with

aemia had not been confirmed.

consequent impair aerobic respiration and cellular en-

ergy utilisation. This impaired cellular functions includ-

2

ing sodium/potassium ATP pump ultimately leading to

Author’s contributions

cellular damage and death. This implies that hypoxae-

2

Kuti BP: Conceptualised the study, collected, analysed

mia should be promptly recognised and managed effi-

the data and wrote the manuscript

ciently particular in sick children to improve survival.

Adetola HH: Collected the data and revised the

We

appreciate the limitation that oxygen saturation

manuscript

(SPO 2 ) was assessed once at

presentation in the study

Kuti DK: Participated in data collection and analysis.

participants and preferred continuous oxygen monitor-

Also revised the manuscript

ing in sick children was not done due to unavailability of

Aladekomo TA: Supervised the conduct of the study and

facilities to do so. Nonetheless, this study has high-

revised the manuscript.

lighted simple easily observable factors that can guide

All the authors approved the final manuscript.

clinicians in resource poor in prompt detection of hy-

Conflicts of interest :

None

poxaemia among emergently ill children with or without

Funding :

None

respiratory features at presentation even in the absence

of

facilities to detect and monitor hypoxaemia.

Acknowledgements

Conclusion

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the clini-

cians and nurses at the children emergency wards of the

In

conclusion, at the emergency room, hypoxaemia was

WGH, Ilesa who participated in the care of the children.

present in one of every two to three children with respi-

References

1.

Duke T, Graham SM, Cherian

5.

Management of the child with a

8.

Orimadegun AE, Ogunbosi

MN, Ginsburg AS, English M,

serious infection or severe mal-

BO, Carson SS.Laman M,

Howie S, et al. The Union

nutrition. World Health Organi-

Ripa P, Vince J, Tefuarani N.

Oxygen Systems Working

zation, Geneva, 2000.

Prevalence and predictors of

Group. Oxygen is an essential

6.

Subhi R, Adamson M, Camp-

hypoxaemia in respiratory and

medicine: a call for interna-

bell H, Weber M, Smith K,

non-respiratory primary diag-

tional action Int

J Tuberc

Lung

Duke T, for the Hypoxaemia in

noses among emergently ill

Dis . 2010; 14(11): 1362 – 8.

Developing Countries Study

children at a tertiary hospital

2.

Qureshi SA. Measurement of

Group. The prevalence of hy-

in

south western Nigeria.

respiratory function: an update

poxaemia among ill children in

Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg .

on

gas exchange. Anaesthesia

developingcountries: a system-

2013; 107:699-705.

& Intensive Care Medicine

atic review. The

Lancet 2009;

9.

Basnet S, Adhikari R, Gurung

2011; 12: 490 – 5.

9: 221-227.

C.

Hypoxemia in children

3.

Wandi F, Peel D, Duke T. Hy-

7.

Emodi J, Ikefuna AN, Ubesie

with pneumonia and its clini-

poxaemia among children in

AC, Chukwu BF, Chinawa JM.

cal predictors. Indian

J Pedi-

rural hospitals in Papua New

Assessment of clinical features

atr. 2006; 73:777 – 81.

Guinea: epidemiology and re-

andhaematocrit levels in detec-

10. Laman

M, Ripa

P, Vince

J,

source availability — a study to

tion ofhypoxaemia in sick chil-

Tefuarani N. Can clinical

support a national oxygen pro-

dren. AJRM

2011; 7(1):

11-13.

signs predict hypoxaemia in

gram. Ann

Trop Paediatr

2006;

Papua New Guinean children

26:277 – 284.

with moderate and severe

4.

Schneider G. Oxygen supply in

pneumonia? Ann

Trop Pedi-

rural Africa: a personal experi-

atr . 2005; 25: 23 – 7.

ence. Int

J Tuberc

Lung Dis

2003; 5: 524 – 6.

280

11. Usen S, Webert M. Clinical

15. Bohnhorst B, Peter CS, Poets

19. Junge S, Palmer A, Green-

signs of hypoxaemia in chil-

CF. Pulse oximeters’ reliability

word BM, Mulholland EK,

dren with acute lower respira-

in

detecting hypoxaemia and

Weber MW. The spectrum of

tory infection: indicators of

bradycardia: comparison be-

hypoxemia in children admit-

oxygen therapy. Int

J Tuberc

tween a conventional and two

ted to hospital in Gambia,

Lung Dis . 2001; 5: 505 – 10.

new generation oximeters. Crit

West Africa. Trop

Med Int

12. Kuti BP, Adegoke SA, Ebruke

Care Med 2000; 28:1565-8.

Health 2006; 11: 367 – 72.

BE, Howie S, Oyelami OA,

16. Oyedeji GA. Socioeconomic

20. Duke T, Blaschke AJ, Sialis

Ota M. Determinants of Oxy-

and cultural background of

S,

Bonkowsky JL. Hypoxae-

gen Therapy in Childhood

hospitalized children in Ilesa.

mia in acute respiratory and

Pneumonia in a Resource-

Niger J Paediatr 1985;

non-respiratory illnesses in

Constrained Region. ISRN

Pe-

13:111‑

8.

neonates and children in a

diatrics. 2013;

Article ID

17. WHO. Pocket book of hospital

developing country. Arch

Dis

435976, 6 pages

care for children: guidelines for

Child 2002; 86:108-112.

13. Ilesa West Local Government

the management of common

Area. Available from: http://

illnesses with limited resources.

www.info@ilesawestlg.os.gov.

World Health Organization,

ng. [Last accessed 23 Septem-

rd

Geneva; 2005

ber, 2015].

18. Well come Trust Working

14. Araoye MO. Subjects Selec-

Party. Classification of infantile

tion. In: Araoye MO, editor.

malnutrition. Lancet

1970;

Research methodology with

2:302- 3.

statistics for health and social

sciences. 1 ed. Ilorin: Natadex

st

2003:115-21.