Copyright 2015 © Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. All Rights Reserved. . Powered by Pelrox Technologies Ltd

ISSN 03 02 4660 AN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA

Quick Navigation

Niger J Paediatr 2016; 43 (2):70 – 77

REVIEW

Elusiyan JBE

Hypoglycaemia in children:

Oyenusi EE

Review of the literature

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i2.2

Accepted: 16th March 2016

Abstract :

Hypoglycaemia is

a

nosed or undertreated hypoglycae-

common metabolic condition in

mia has been found to increase mor-

Elusiyan JBE

(

)

children. It often presents urgent

tality in children when it is present.

Department of Paediatrics and

and therapeutic challenges and it

This review sought to review the

Child Health, Obafemi Awolowo

University, Ile-Ife. Nigeria.

has been documented to affect

subject of hypoglycaemia in chil-

Email: jelusiyan@yahoo.co.uk

many childhood conditions. Its

dren and calls for testing for it in all

clinical presentation is not classi-

sick and admitted children.

Oyenusi EE

cal and requires a high index of

Department of Paediatrics,

suspicion for an early diagnosis

College of Medicine, University of

and prompt management. Undiag-

Lagos/Lagos University Teaching

Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria.

Introduction

whether ‘asymptomatic’ hypoglycaemia causes neuro-

logical

dysfunction and damage or not.

10

The term hypoglycaemia refers to blood glucose level

The plasma glucose concentration is normally main-

below normal. Most of the time low blood glucose con-

tained within a relatively normal range of 3.9 to

centration is not associated with the development of the

8.3mmol/L (70 to 150mgdl), despite wide variations in

classic clinical manifestations of hypoglycaemia. The

glucose influx and efflux such as those that follow meals

and occur during exercise . There is however general

11

absence of clinical symptoms does not indicate that glu-

cose concentration is normal or has not fallen below

agreement that a value of blood glucose that is less than

optimal level for maintaining brain metabolism. Hypo-

1

2.2mmol/L (40mgdl) represents hypoglycaemia and

most of the work on hypoglycaemia

3,12-14

glycaemia in the paediatric age group is a common clini-

in

the literature

cal finding and is associated with a wide variety of dis-

are based on this cut-off value. Two factors which are

orders . Even in the Tropics, there is a growing aware-

2

frequently overlooked when interpreting the glucose

ness that hypoglycaemia can complicate many child-

concentrations are the analytic method used and whether

hood illnesses. This has necessitated several recent

3

whole blood or serum (plasma) was examined. When

work on the problem of Hypoglycaemia among Nigerian

whole blood is used, the value of blood sugar below

children.

4-6

The

condition often presents urgent diagnos-

2.2mmol/L represents hypoglycaemia as opposed to

tic and therapeutic challenges.

7

2.5mmol/L if plasma (or serum) sample is used. This is

because in individuals with a normal haematocrit, fast-

The major long-term sequelae of severe, prolonged hy-

ing whole blood glucose concentration is approximately

poglycaemia are neurologic damage resulting in mental

8 to

15% less than plasma glucose due to the fact that

retardation, transient cognitive impairment, neurological

the

water content of plasma (93%) is approximately

12%

higher than that of whole blood.

15-17

deficit and recurrent seizure activity. Subtle effects on

8

In

most clini-

personality are also possible but have not been clearly

cal

laboratories plasma or serum is used for most glu-

defined.

9,10

Moderate hypoglycaemia has been shown in

cose determination whereas most bedside methods for

neonates to be associated with a considerable increase in

self-monitoring of glucose use whole blood.

adverse neurodevelopmental effects.

10

Epidemiology

Definition of hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia is said to occur more commonly in pae-

diatric patients than in adults. There are many studies

18

Although there is a general agreement on the need to

maintain blood glucose concentrations above a ‘critical’

on

neonatal hypoglycaemia probably engendered by the

level in young children and neonates, there is no agree-

increased vulnerability of the immature neonatal brain to

damage by hypoglycaemia.

19,20

ment among practising paediatricians and authors as to

the lowest safe concentration of blood glucose.

11

The

difficulty with the definition is understandable in view

Hypoglycaemia has also been reported in children be-

yond the neonatal period

3-6,21

of

the lack of reliable clinical signs when the blood glu-

.

It has been found to also

complicate many emergency paediatric admissions.

3-6,21

cose

concentrations fall in newborn infants and young

children and in view of the continuing controversy over

The

prevalence of hypoglycaemia in emergencies varies

71

from one practice to another.

the brain accounts for almost 100% of total basal glu-

In

Birmingham , a rate of 6.54/100,000 visits was

21

cose turnover making most of the endogenous glucose

found among children seeking care at the emergency

production (EGP) in infants and young children ac-

counted for by brain metabolism , unlike in neonates

1

department while Solomon et al found a rate of 7.1% in

3

Mozambique. More recent studies done in paediatric

where EGP provides approximately one third of glucose

needs. Thus brief hypoglycaemia may cause profound

35

emergency admissions of some West African countries

equally documented the occurrence of hypoglycaemia.

22-

brain dysfunction, while prolonged severe hypoglycae-

24.

mia may eventuate in brain death. Therefore, to main-

11

Prevalence rates of 6.4% in Ile-Ife by Elusiyan et al

22

and 5.6% in Lagos by Oyenusi et al both in Nigeria and

23

tain normal blood glucose concentration and prevent

a

rate of 13% by Ameyaw et al in Kumasi, Ghana re-

24

precipitous falls to levels that impair brain function,

spectively were reported. Other studies such as that done

humans have evolved an elaborate gluco-regulatory sys-

by

Osier et al

25

reported a prevalence of 7.3% among

tem.

11

The prolonged interval between onset of symp-

paediatric admissions in Kenya while a prevalence rate

toms and correct diagnosis reported in most studies indi-

of

18.6% was documented by Wintergerst et al among

26

cates that the possibility of symptomatic spontaneous

patients admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit of a

hypoglycaemia has not received proper consideration

tertiary hospital in California, United States.

early in the course of many clinical situations. There-

fore, whenever repetitive, episodic, bizarre manifesta-

Some authors reported the prevalence of hypoglycaemia

tions occur at any time, whether after a fast, after an

in

studies designed to investigate specific disease enti-

acute illness or shortly after meals, a blood glucose level

ties rather than cohorts ofchildren presenting to the

should be obtained at the time of the symptoms. Only in

emergency room or admitted into the wards with diverse

this way can the diagnosis be established and therapy

problems. For instance, Familusi and Sinnette

27

docu-

instituted early, thus avoiding the sequelae of prolonged

mented aprevalence rate of 13% in children presenting

hypoglycaemia.

36

with febrile convulsions at the emergency ward in

Ibadan, Nigeria. Among children with diarrhoea, the

Elucidation of the physiology of glucoregulation in gen-

prevalent rates of hypoglycaemia reported were 4.5%

eral and of glucose counter regulation in particular has

by

Bennish et al and Bhattacharya et al 40%, respec-

13

28

provided major insights into the pathophysiology of

tively in Asia while in Nigeria, Ntia et al

29

and

Ony-

hypoglycaemia in humans. Nevertheless, there are major

iriuka et al reported prevalence rates of 4% and 4.9%

30

gaps in our understanding of the causes, mechanisms

and management of many hypoglycaemic states. In the

11

respectively.

fasted individual, the maintenance of a normal blood

Another clinical condition in which the prevalence of

glucose level is dependent upon (1) adequate supply of

hypoglycaemia has been widely investigated ismalaria.

endogenous gluconeogenic substrates like amino acids,

Comparable prevalence rates of hypoglycaemia between

glycerol, and lactate (2) functionally intact hepatic gly-

16-17% were documented by English et al

12

in

Kenya,

cogenolytic and gluconeogenic enzyme systems, and (3)

Genton et al in New Guinea and Nwosu et al in La-

31

32

a

normal endocrine system for integrating and modulat-

gos, Nigeria among children with severe malaria. How-

ing these two processes. The adult human being is quite

ever, Onyiriuka et al in Benin, Nigeria and White et al

33

capable of maintaining a normal blood glucose level

in

Gambia

14

reported higher prevalence rates of 18.3%

even when totally deprived of calories for weeks or, in

and 32% respectively in children with severe malaria.

the case of obese subjects, for months. In contrast, the

normal child exhibits a progressive fall in blood glucose

Pathophysiology

to

hypoglycaemic levels when fasted for even short peri-

ods (e.g. 24 to 48 hours).

2,37

The

reasons for the differ-

Glucose plays a central role in mammalian fuel econ-

ence are not clear, but it may be that the young individ-

omy and is a source of energy derivable from glycogen,

ual, when fasting, is unable to supply sufficient glucose

fats and protein. Glucose is an immediate source of

34

to

meet the obligatory demands of the body for glucose.

energy providing 38 moles of ATP/mole of glucose oxi-

Although most tissues have the enzyme systems re-

dized. Blood glucose level reflects a dynamic equilib-

34

quired to synthesize glycogen (glycogen synthase) and

rium between the glucose input from dietary sources

to

hydrolyse glycogen (phosphorylase), only the liver

plus that released from the liver and kidney and the glu-

and kidneys contain glucose-6-phosphatase, the enzyme

cose uptake that occurs primarily in the brain, muscle,

necessary for the release of glucose into the circula-

tion . The liver and kidneys also contain the enzymes

11

adipose tissue and blood elements.

11,34

Hypoglycaemia

thus represents a defect in one or several of the complex

necessary for gluconeogenesis (including the critical

interactions that normally integrate glucose homeostasis

enzymes pyruvate carboxylase, phosphenol pyruvate

carboxykinase, and fructose-1,6- bisphophatase). This

11

during feeding and fasting.

shows the importance of these organs in glucose ho-

The maintenance of the plasma glucose concentration is

meostasis, particularly with gluconeogenesis. In dis-

critical to survival because plasma glucose is the pre-

eased states affecting these organs, hypoglycaemia will

dominant metabolic fuel utilized by the central nervous

be

a major problem unless adequate intake of glucose is

system (CNS) under most conditions. The CNS can

maintained.

neither synthesize glucose nor store more than a few

minutes’ supply of glucose.

11

Glucose metabolism by

There are multiple potential metabolic fates of glucose

72

It

may be stored as glycogen

(deficient endogenus production), or both.

11,38

transported into cells

11

There are

majorly. It may undergo glycolysis to pyruvate, which in

conditions in which glucose utilization is increased

turn can be oxidized to carbon-dioxide and water via the

markedly (e.g. exercise, large tumours, infections) and

tricarboxylic acid cycle, converted to fatty acids (and

in

which renal losses occur at physiological plasma glu-

cose concentration (i.e. renal glycosuria) . However,

11

stored as triglycerides), or utilized for ketone bodies

(acetoacetate, B-hydroxylbutyrrate), or cholesterol syn-

because of the normal capacity of the liver to increase

thesis (Fig.1). Finally, glucose may be released into the

11

glucose production several fold, clinical hypoglycaemia

is

rarely the result of excessive glucose efflux alone.

11

circulation for the immediate metabolic need of the

body. External losses are normally negligible.

11

Rather, it is commonly the result of hepatic glucose pro-

duction that is either decreased absolutely or inappropri-

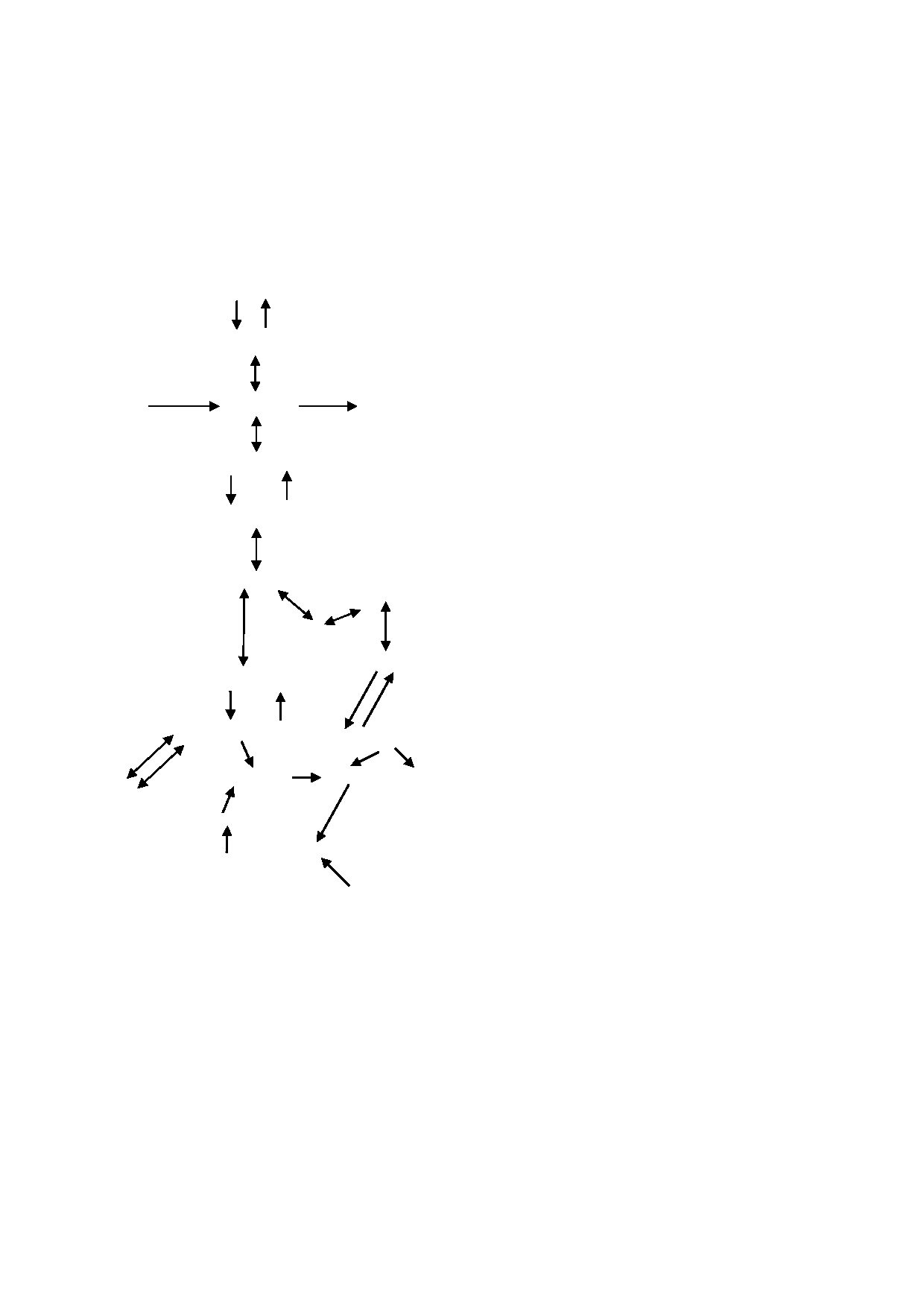

Fig 1: Schematic

representation of

glucose metabolism

11

ately low relative to the rate of glucose utilization .

11

Glycogen

In

African children with malaria and other infections, an

(2)

(9)

impairment in hepatic gluconeogenesis in the presence

of

adequate levels of precursors has been considered the

Glucose-1-p

most likely mechanism

12,14,39

.

(1)

(8)

Other suggested possible mechanisms of hypoglycaemia

in

malaria include accelerated tissue metabolism;

40

Glucose

Glucose-6-P

Glucose

the

metabolic requirements of the parasites and malabsorp-

tion of glucose probably secondary to changes in

Fructose-6-P

splanchnic blood flow owing to a heavy parasite load in

vessels

41,42

.

Sequestration of parasitized red cells in the

(3)

(7)

venules and capillaries of deep tissues may impair local

circulation

43,44

.

This may necessitate a transition to an-

Fructose-1,6-P

aerobic glycolysis releasing lactate and increasing glu-

cose consumption . High serum lactate levels in pa-

45

tients with malaria is thought to indicate lactate produc-

Triose-P

tion by the malaria parasites and anaerobic glycolysis in

TRIGLYCERIDES

tissues where the blood vessels have a heavy parasite

infestation

39,43,46

.

Impaired hepatic gluconeogenesis

GLYCEROL

could also lead to high lactate levels from the Cori cy-

cle . Furthermore, the reduced dietary intake and the

45

FATTY ACIDS

Phosphoenolpyruvate

associated vomiting as well as the increased metabolic

requirement caused by fever in malaria are other sug-

(4)

(6)

gested mechanisms of hypoglycaemia .

14

Pyruvate

AcetylCoA

Mechanisms of hypoglycaemia in infections

(5)

Oxaloacetate

Citrate

KETONES

Hypoglycaemia in other infective process like pneumo-

nia and septicaemia has been attributed to the increased

LACTATE

TCA

cycle

metabolic requirement caused by fever as stated earlier

resulting in increased peripheral glucose utilization.

47

ALANINE

a-Ketoglutarate

Studies have also shown that increased peripheral utili-

zation of glucose appears to be the primary mechanism

Glutamine

for hypoglycaemia in neonates with bacteraemia

48,49

.

Inhibition of gluconeogenesis is considered to be pri-

1.

Hexokinase/Glucokinase

marily responsible for the hypoglycaemia in septicaemia

in

a report by Filkins and Cornell.

50

2.

Glycogen synthase

Endotoxins pro-

3.

Phosphofructokinase

duced by organisms in infectious processes have also

4.

Pyruvate kinase

been known to stimulate increased insulin secretion

causing hypoglycaemia

47,50,51

5.

Pyruvate carboxylase

.

These toxins can also

6.

Phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylkinase

cause hypoglycaemia by contributing directly to deple-

tion of hepatic glycogen stores . Hypotension and de-

47

7.

Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase

8.

Glucose-6-phosphatase

creased tissue perfusion in septic shock increase periph-

9.

Phosphorylase

eral utilization of glucose because the shift to anaerobic

from aerobic metabolism requires 18 times more glu-

cose to produce the same amount of energy (ATP) .

52

Mechanisms of hypogyclaemia

Several mechanisms are known to cause hypoglycaemia

Mechanisms of hypoglycaemia in diarrhoeal disease

in

children.

Theoretically hypoglycaemia could result

from excessive glucose efflux (excessive glucose utiliza-

Various factors ranging from hyperinsulinaemia,

tion or external losses), deficient glucose influx

hypoxia, fasting, malnutrition, ketosis and impairment

73

of

gluconeogenesis have been suggested as the mecha-

glucose.

nisms of hypoglycaemia in diarrhoeal diseases

13,50,53

.

2.

Exact cause unknown – Small for gestational age,

Bennish et al noted that plasma levels of counter-

13

fetal distress, any sick newborn Neonatal sepsis,

regulatory hormones (glucagon, epinephrine and norepi-

Neonatal tetanus etc.

nephrine) were appropriately elevated while gluconeo-

B)

Persistent (Neonatal, Infancy and early child hood 0

genic substrates were inappropriately low in the

-2yrs)

children with diarrhoea and hypoglycaemia suggesting

1.

Hyperinsulinism – Islet cell hyperplasia, Nes-

that

the hypoglycaemia observed in such patients is of-

sidioblastosis,

Islet cell adenoma, leucine sensitiv-

ten

due to the failure of gluconeogenesis.

13

ity, Beckwith – Wieldeman syndrome

2.

Glycogen Storage disease

Mechanisms of hypoglycaemia in malnutrition

3.

Defect in gluconeogenesis

4.

Hormone deficiency – Congenital Adrenal Hyper-

During

severe malnutrition, gluconeogenic substrates

plasia, hypothyroidism etc.

such as alanine and lactate are significantly reduced

2,54

.

5.

Miscellaneous – Galactosaemia, Fructose – intoler-

The

capacity to generate glucose by gluconeogenesis is

ance, salycylate intoxication, Reye syndrome, hepa-

markedly diminished and alternate fuels such as ketones

titis

or

lactate are also reduced

2,54

.

The resultant fatty infiltra-

tion of the liver causes glycogen and gluconeogenic

Older Children 1-18 years: The predominant

condi-

substrate depletion. There is also defect in glyco-

tions complicated by hypoglycaemia as seen in the trop-

genolytic pathways and limited lipolysis .

55

ics include severe malaria, septicaemia, pneumonia and

protein-energy malnutrition.

22-25

Other cause

include

Mechanisms of drug-induced hypoglycaemia

side effects of drugs or drug overdosages, use of tradi-

tional concoctions as mentioned earlier amongst others.

Hypoglycaemia can also be caused by medications ad-

Hyperinsulinism, secondary to therapy of diabetes or

ministered to patients in the course of an illness. Drug

islet cell adenoma is also an important cause of hypogly-

therapy for malaria particularly quinine, may cause hy-

caemia.

57-59

poglycaemia by stimulating insulin release

.

The use

of

other cinchona alkaloids like quinidine has also been

Persistent hypoglycaemia

associated with hypoglycaemia . Drug intoxications in

60

children can also cause hypoglycaemia. Excessive doses

There are few examples of persistent hypoglycaemia in

of

salicylates (4 to 6g/day) can distort multiple bio-

children. These include persistent hyperinsulinaemic

chemical reactions to produce metabolic acidosis, hypo-

hypoglycaemia and ketotic hypoglycaemia. It must be

glycaemia or hyperglycaemia

61,62

.

Accelerated utiliza-

pointed out that these classes of hypoglycaemia are

tion of glucose due to augmentation of insulin secretion

rarely reported in the tropics probably due to problems

by

salicylates and possible interference with gluconeo-

with diagnosis.

genesis may both contribute to hypoglycaemia .

62

Accidental ingestion of ethanol is a common cause of

Hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia is a heterozygous

poisoning in children in our environment.

63

In

ethanol

condition in which insulin secretion becomes unregu-

intoxication, the liver metabolizes ethanol as a preferred

lated and its production persists despite low blood glu-

cose levels . It is the most common cause of severe and

15

fuel, and generation of reducing equivalents during the

persistent hypoglycaemia in neonates and children

1,15

oxidation of ethanol alters the NADH/NAD ratio that is

.

essential for certain gluconeogenic steps . As a result,

15

This could be monogenic or syndromic.Congenital hy-

gluconeogenesis is impaired and hypoglycaemia may

perinsulinism (HI) has been described under various

ensue if glycogen stores are depleted . Three to five

15

terms in the past including "idiopathic hypoglycaemia of

percentage of children with alcohol intoxication will

infancy,"

"leucine-sensitive

hypoglycemia,"

or

"nesidioblastosis."

71

have hypoglycaemia . Overdosage of other drugs such

64

It

has now become apparentt that

as

insulin and oral hypoglycaemic agents can also cause

HI

is caused by genetic defects in the pathways that

regulate pancreatic β -cell insulin secretion . Several

71

hypoglycaemia

65,66

.

candidate genes mutations have been identified as re-

Cow’s urine concoction (CUC) is a mixture consisting

sponsible for CHI

including ABCC8, KCNJ11,

GLUD1, GCK, HADH1 .

71

of

cow’s urine, tobacco leaves, garlic leaves, basil

In

a cohort from Tur-

leaves, lemon juice, rock salt and bulbs of onion . It is

67

key,mutations in the ABCC8 gene were found to be the

most common cause of CHI . Management of HI is

72

commonly used in Western Nigeria in the belief that it

controls convulsions or prevents febrile convulsions in

very difficult as current facilities for genetic diagnosis

children but it is known to cause severe hypoglycae-

and appropriate imaging are limited only to very few

mia

27,63,67

.

This could be due to the hypoglycaemic activ-

centres in the world and frequently requires difficult

and garlic contained in the mixture.

70

ity

of onions

68,69

choices, such as near-total pancreatectomy and/or highly

intensive care with continuous tube feedings

71,73

Some

Common aetiology of hypoglycaemia in Neonates

1

patients may respond to treatment with diazoxide, a

A)

Transient 0-7 days

KATP channel agonist while others may also develop

1.

Hyperinsulinism – Infant of Diabetic mothers,

diabetes in later life following the surgery.

erythroblastosis, discontinuation of intravemous

Ketotic hypoglycaemia is said to be the most common

74

76,77

form of childhood hypoglycaemia . It is also referred to

74

diagnosing hypoglycaemia in studies by the authors

.

as

ketotic hypoglycaemia of infancy and classically

A

brand of glucometer was found to have a sensitivity of

manifest between the ages of 18 months and 5 years and

96.00% (95% CI =81.81%-99.80%) and a specificity of

may remit spontaneously before the age of 10 years.

74

96.46% (95% CI=94.17%-98.02%).

76

The predictive

Typical history is of a child who may miss a meal due to

index of a positive test of 64.9% and the predictive in-

dex for a negative test of a 97.72%. An equally high

76

an

infection usually an upper respiratory tract infection

and then develops hypoglycaemia form of childhood

74

specificity (99.8%) and moderate sensitivity (75%) of

hypoglycaemia . It is also referred to as ketotic hypo-

74

another brand of glucometer were observed with high

glycaemia of infancy and classically manifest between

positive predictive and negative predictive values of

94.7% and 98.7% respectively . However it remains

77

the ages of 18 months and 5 years and may remit spon-

taneously before the age of 10 years. Typical history is

74

imperative that at least, a sample should be sent to the

of

a child who may miss a meal due to Convulsion may

laboratory for confirmation. Furthermore, in newborns,

occur at the time of hypoglycaemia and a presumptive

hypoglycaemia should be tested for in all infant of dia-

diagnosis is made by documenting a low blood sugar in

betic mothers irrespective of weight at birth and gesta-

association with ketonuria, ketonaemia and typical

tional age and in all babies born with a birth weight of

4kg and above . Children on nil per

oris too should also

78

symptoms of hypoglycaemia. Ketotic hypoglycaemia is

prevented by limiting the duration of fasting and main-

have regular blood glucose monitoring. Once hypogly-

taining a high glucose intake during illnesses.

74

caemia is diagnosed, blood glucose should be deter-

mined frequently 30 minutes after initial correction and

Clinical features of hypoglycaemia

then hourly, 2 hourly and 4 hourly after obtaining two

normal readings form of childhood hypoglycaemia . It

78

74

The clinical manifestations of hypoglycaemia are non-

is

also referred to as ketotic hypoglycaemia of infancy

specific . In addition, they vary among individuals and

11

and classically manifest between the ages of 18 months

may vary from time to time in the same individuals

11

and 5 years and may remit spontaneously before the age

of

10 years . Typical history is of a child who may miss

74

form of childhood hypoglycaemia . It is also referred to

74

as

ketotic hypoglycaemia of infancy and classically

a

meal due to

manifest between the ages of 18 months and 5 years and

Another benefit of bedside determination of blood glu-

may remit spontaneously before the age of 10 years.

74

cose is to prevent hyperglycaemia which may be caused

Typical history is of a child who may miss a meal due to

by

unnecessary glucose administration to children that

Clinical manifestations of hypoglycaemia fall into two

are normoglycaemic or may even be hyperglycae-

mic

24,25,79,80

categories. The first category includes features associ-

1

.

ated with the activation of the autonomic system and

epinephrine release usually seen with a rapid decline in

Treatment of hypoglycaemia

blood glucose.

1,15

,

These features are sweating, trem-

bling, anxiety, nervousness, weakness, hunger, nausea

The primary objective of treatment is to restore the

blood glucose concentration to the normal range. The

75

and vomiting.

1,15

The

second category includes features

due

to decreased cerebral glucose utilization usually

hypoglycaemic child should receive an immediate bolus

associated with slow decline in blood glucose level or

of

0.25g/kg of dextrose as a concentrated solution (10-

prolonged hypoglycaemia.

15,16

These features are head-

25%) over a minute

1,15,22,23,75,81

.

This should be followed

aches, visual disturbances, lethargy, lassitude, restless-

by

a continuous dextrose infusion at 8-10mg/kg/min in

ness, irritability, difficulty in thinking, inability to con-

order to avoid rebound hypoglycaemia which may occur

within 30 minutes of the bolus injection

1,15,22,75

centrate and mental confusion. Others include somno-

.

Glucose

lence, stupor, prolonged sleep, loss of consciousness,

level should be determined at 15 minutes after the bolus

coma, hypothermia, twitching, convulsion and bizarre

has been given and while the maintenance glucose infu-

neurological signs (motor and sensory), loss of intellec-

sion is running. If hypoglycaemia recurs at this time, a

tual ability, personality changes and outbursts of temper.

bolus of 0.5g/kg of glucose may be given and the

There could also be psychological disintegration with

glucose infusion increased by 25-50% until normogly-

caemia is achieved

15,75

manic behaviour, depression, psychosis, permanent

.

High volume rates carry the risk

mental or neurological damage

1,15

.

of

fluid overload manifest in pulmonary oedema and/or

Therefore it is important to consider the possibility of

heart failure. This can be minimized by the use of a cen-

tral venous catheter and concentrated solutions . Enteric

75

hypoglycaemia in any situation in which the signs or

symptoms are compatible with an inadequate supply of

feeding is encouraged if there are no contraindications.

glucose to the brain .

75

The glucose infusion and blood glucose determination

are discontinued after two consecutive normal blood

Diagnostic work up

glucose levels measured 30 minutes apart and patient is

eating well

22,23

.

Infant of diabetes mothers should be fed

within 30 minutes of birth by the most possible route .

78

Any

child that is sick enough to be admitted to the hos-

pital should be screened for presence of hypoglycaemia.

This

is very important because most times, hypoglycae-

Complications of hypoglycaemia

mia

is asymptomatic and when symptoms are present,

they

are non-specific. Bedside meters have been vali-

A

strong association between hypoglycaemia and in-

dated and found to be highly sensitive and specific for

creased mortality and morbidity has been documented

75

86

by

several authors

3,22-26,82

.

Hypoglycaemia appears to be

thors further noted that the hypoglycaemia of hyperin-

a

function of the severity of illness in childhood and

sulinism is particularly dangerous because it is associ-

more severely ill children will be more likely to die than

ated with total absence of all brain fuels (low plasma

less severely ill ones.

22,23

Hypoglycaemia is also a major

lactate, ketones and glucose) and thus more easily pre-

disposes the individual to brain damage . The risk of

86

indicator of a poor prognosis in different disease entities

like cerebral malaria and gastrointestinal infections

13,29-

brain damage from hypoglycaemia is highest when the

33,39,83,84

.

Hypoglycaemia has been shown to be inde-

hypoglycaemia is prolonged or recurrent and the effects

have been shown to be more in the younger child .

75

pendently associated with speech and language impair-

ments and impairment of non-verbal functioning.

83

Nwosu et al reported that neurological sequelae were

32

about twice as common in children with cerebral malaria

and concomitant hypoglycaemia. The most frequently

Conclusion

occurring sequelae were cortical blindness, monoparesis,

aphasia, hemiparesis, generalized hypotonia, decerebrate

Hypoglycaemia is a common complication of many

syndrome and cerebellar ataxia

33,39

.

childhood diseases with varied pathophysiological

In a

retrospective multicentre study, Lucas et al found

10

mechanisms. It is amenable to treatment but can cause

that moderate hypoglycaemia (<2.6mmol/L) may have

permanent neurological sequelae if prolonged or not

serious developmental consequences if present for five

treated promptly. Children who present in emergency

or

more days during the first two months of life. This

are at special risk of hypoglycaemia. A high index of

provides compelling evidence that even asymptomatic

suspicion should be maintained when evaluating very

86

hypoglycaemia could be harmful . Menniet al

85

re-

sick children for early detection and subsequent prompt

ported that hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia was asso-

and aggressive management.

ciated with psychomotor retardation, learning disability,

seizures and diverse neurological sequelae. The au-

Reference

1.

Sperling MA. Hypoglycaemia. In:

7.

Verrotti A, Fusilli P, Pallotta R,

14.

White NJ, Marsh K, Turner RC, et

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Ar-

Morgese G, Charelli F. Hypogly-

al.

Hypoglycaemia in African

ron

AM (Eds). Nelson Textbook of

caema in childhood: a clinical

Children with severe malaria.

Lan-

Peadiatrics, 15 edition. Philadel-

th

approach .

J Pediatr,

Endocrinol-

cet 1987; 1: 708 – 711.

phia. W.B. Saunders, 1996, p 420

Metab 1998; (Suppl 1): 147-52.

15.

Thornton TS, Finegold DN,

–

430.

8.

Jarjour IT, Ryan CM, Becker DJ.

Stanley CA, Sperling MA. Hypo-

2.

Pagliara AS, Kaul IE, Haymond M

Regional cerebral blood flow dur-

glycaemia in the infant and child.

and

Kipnis DM. Hypoglycaemia in

ing

hypoglycaemia in children

In:

Sperling MA (editor) Paediatric

Endocrinology. 2 edn. Philadel-

nd

infancy and childhood. J

Pediatr

with IDDM. Diabetologia

1995;

1973; 82: 365-379.

38: 1090-1095.

phia: Saunders; 2002.pp.135-59.

3.

Solomon T, Felix TM, Samuel M

9.

Bondi FS.. The incidence and out-

16.

Sacks DB. Carbohydrates. In:

et

al. Hypoglycaemia in Paediatric

come of neurological abnormali-

Burtis CA, Ashwood ER(editors).

admissions in Mozanbique. Lancet

ties in childhood cerebral malaria:

TietzFundamentals of Clinical

Chemistry. 5 edition. London:

th

1994; 343: 149-50.

a

long term follow-up of 62 survi-

4.

Elusiyan JBE. Hypoglycaemia in

vors. Trans

R Soc

Trop Med

Hyg

WB

Saunders; 2001.pp.776-85.

Emergency Paediatric admissions.

1992; 86: 17-19R

17.

Ajala MO, Oladipo OO, Fasan-

Dissertation submitted for the

10.

Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ. Ad-

made O, Adewole TA. Laboratory

Fellowship of the West African

verse neurodevelopmental out-

assessment of three glucometers.

College of Physician (FWACP).

come of moderate neonatal hypo-

Afr J Med Sci 2003; 32:279-82.

Oct. 2004.

glycaemia. B

M J

1988; 297:

1304

18.

Ltief AN, Schwack WF. Hypo-

5.

Jaja T. Hypoglycaemia in emer-

-1308.

glyaecamia in infants and children.

gency admission at University of

11.

Cryer PE. Glucose homeostatis

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am

Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital.

and

hypoglycaemia. In: Wilson

1999; 28: 619-46.

Dissertation submitted for the

JD,

Foster DW (eds). Willams

19.

Omene JA. The Incidence of Neo-

Textbook of Endocrinology, 8

th

fellowship of the National Post

natal hypoglycaemia in Benin.

graduate Medical College of Nige-

edition. Philadelphia,

WB Saun-

Niger J Paed 1977; 4: 19-23

ria

(FMCPaed) 2008.

ders, 1992: 1223-1253.

20.

Njokanma OF, Fagbule D. Inci-

6.

Oyenusi EE. Hypoglycaemia in

12.

English M, Wale S, Binns G,

dence, aetiology and manifestaions

children aged one month to 10

Mwangi I, Sauerwein H, Marsh K.

of

neonatal hypoglycaemia. Niger

years admitted to the Children’s

Hypoglycaemia on and after ad-

J Paed 1994; 21: 26-31.

Emergency Centre of the Lagos

mission in Kenyan children with

21.

Pershad J, Monroe k, Atchison J.

University Teaching Hospital.

severe malaria. Q

J Med

1988; 91:

Childhood Hypoglycaemia in an

Dissertation submitted for the

191-197.

urban emergency department:

fellowship of the National Post

13. Bennish

ML, Azad

AK, Rahman

Epidemiology and a diagnostic

graduate Medical College of Nige-

O,

Phillips RE. Hypoglycaemia

approach to the problem.

Paediatr

ria

(FMCPaed) Nov 2011.

during diarrhea in childhood,

Emerg care 1998; 14: 268-71.

Prevalence, Pathophysiology and

22.

Elusiyan JBE, Adejuyigbe EA,

Outcome. N

Engl J

Med 1990;

Adeodu OO. Hypoglycaemia in

a

322: 1357 – 1363.

Nigerian Paediatric Emergency Ward.

J Trop Pediatr; 2006; 52: 96-102.

76

23.

Oyenusi EE, Oduwole AO,

33.

Onyiriuka AN, Peters OO,

45.

White NJ, Warrell DA, Looareesu-

Oladipo OO, Njokanma OF, Ese-

Awaebe PO. Hypoglycaemia at

wan

S, Chanthavanich P, Phillips

zobor CI. Hypoglycaemia in chil-

point of hospital admission of

RE,

Pongpaew P. Pathophysiologi-

dren aged 1 month to 10 years

children below five years of age

cal

and prognostic significance of

admitted to the children emer-

with falciparum malaria: preva-

cerebrospinal fluid lactate in cere-

gency center of Lagos University

lence and risk factors. Niger J

bral malaria. Lancet

1985; 1:776-

Teaching Hospital, Nigeria.

South

Paed 2013; 40:238-242.

8.

Africa J. Child Health. 2014; 8:

34.

Ganong WF. Review of Medical

46.

Kawo NG, Mseng AE, Swai

Physiology 17 edition. Connecti-

th

107-11.

ABM, Chuwa LM, Alberti

24.

Ameyaw E, Amponsah-Achiano

cut: Appleton & Lange;

KGMM, Mclarty DG. Specificity

K,

Yamoah P, Chanoine JP. Ab-

1995.pp.255-89.

of

hypoglycaemia for cerebral

normal blood glucose as a prog-

35.

Tyrala EE, Chen X, Boden G.

malaria in children. Lancet

1990;

nostic factor for adverse clinical

Glucose metabolism in the infant

336:454-7.

outcome in children admitted to

weighing less than 1100grams. J

47.

Miller SI, Wallace RJ Jr, Musher

the

paediatric emergency unit at

Pediatr 1994; 125: 283-7.

DM,

Septimus EJ, Kohl S, Baughn

KomfoAnokye Teaching Hospital,

36.

Bondi FS.. The incidence and out-

RE.

Hypoglycaemia as a manifes-

Kumasi, Ghana. Int

J Paed

Volume

come of neurological abnormali-

tation of sepsis. Am

J Med

1980;

2014, Article ID 149070, 6 pages

ties in childhood cerebral malaria:

68:649-54.

http://

a

long term follow-up of 62 survi-

48.

Yeung CY. Hypoglycaemia in

dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/149070

vors. Trans

R Soc

Trop Med

Hyg

neonatal sepsis. J

Pediatr 1970;

25.

Osier FHA, Berkley JA, Ross A,

1992; 86: 17-19R.

77:812-7.

Sanderson F, Mohammed S, New-

37.

Senior B, Loridan L. Gluconeo-

49.

Yeung CY, Lee VWY, Yeung

ton

CRJC. Abnormal glucose

genesis and insulin in the Ketotic

MB.

Glucose disappearance rate in

concentrations on admission to a

variety of Childhood hypoglycae-

neonatal infection. J

Pediatr 1973;

rural Kenyan district hospital:

mia

and in control Children. J

82:486-9.

prevalence and outcome. Arch Dis

Pediatr 1969; 74: 529-39.

50.

Filkins JP, Cornell RP. Depression

Child 2003; 88:621-5.

38.

Otto BE, Jarosz CP, Szirer G. Ho-

of

hepatic gluconeogenesis and the

26.

Wintergerst KA, Buckingham B,

meostasis disturbances – hypogly-

hypoglycaemia

of endotoxic

Gandrud L, Wong BJ, Kache S,

caemia in newborns and infants.

shock. Am

J Physiol

1974;

Wilson DM. Association of hypo-

Przeglad Lekarski 2001; 58:79 -

227:778-81.

glycemia, hyperglycemia and glu-

81.

51.

Yelich MR, Filkins JP. Mechanism

cose variability with morbidity and

39. Taylor

TE, Molyneux

ME, Wirima

of

hyperinsulinaemia in endotoxi-

deaths in the pediatric intensive

JJ,

Fletcher A, Morris K. Blood

cosis. Am

J Physiol

1980; 239:

care unit. Pediatrics

2006;

glucose levels in Malawian chil-

E156-161.

118:173-9.

dren before and during the admini-

52.

Nelson DL, Cox MM. The mo-

27.

Familusi JB, Sinnette CH. Febrile

stration of intravenous quinine for

lecular logic of

life. In: David L,

convulsion in Ibadan children.

Afr

severe falciparum malaria. N Engl

Nelson DL (editors). Lehninger Princi-

ples of Biochemistry.3 edn New York:

rd

J MedSci 1971; 2: 135-149.

J Med 1988; 319: 1040-46.

28.

Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya

40.

Warrel DA,Veall N,Chanthavanich

Worth; 2000 pp.3-19.

MK,

Dutta D, Garg S, Mukhopadhyay

P,Karbwang J,White JN, Looaree-

53.

Hirschorn N, Lindenbaum J,

AK,

Deb M Moitra A , Nair GB.

Vibrio

suwan S, Phillips RE, Pongpaew

Greenough WB III, Alam SM.

cholerae0139 in Canada. Arch Dis

P.

Cerebral anaerobic glycolysis

Hypoglycaemia in children with

Child 1994; 71:161-2.

and

reduced cerebral oxygen trans-

acute diarrhoea. Lancet

1966;

29.

Ntia HN, Anah MU, Udo JJ, Ewa

port in human cerebral malaria.

2:128-32.

AU,

Onubi J. Prevalence of hypo-

Lancet 1988; 2: 534-8.

54.

Wharton B. Hypoglycaemia in

glycaemia in under-five children

41.

Walter WK, Myron JT. Malab-

children with kwarshiorkor.

Lancet

presenting with acute diarrhoea in

sorption in plasmodium falciparum

1970; 1:171-3.

University of Calabar Teaching

malaria. Am

J Trop

Med Hyg

55.

Akesode FA, Babalola AA. Hypo-

Hospital, Calabar. Niger

J Paed

1972; 21:1-5.

glycaemic response to exogenous

2012; 39: 63-66.

42. Molyneux ME,

Looareesuwan S,

insulin in children with protein

30.

Onyiriuka AN, Awaebe PO,

Menzies IS, Grainger SL, Phillips

energy malnutrition. Niger

J Paed

Kouyaté M. Hypoglycaemia at

RE,

Wattanagoon Y, Thompson

1987; 14:45-9.

point

of hospital admission of

RP,

Warrell DA. Reduced hepatic

56.

White NJ, Warrel DA, Chantha-

under-five children with acute

blood flow and intestinal malab-

vanich P, Loareesuwan S, Warrel

diarrhoea: prevalence and risk

sorption in severe falciparum ma-

MJ,

Krishna S, Williamson DH,

factors. Niger

J Paed

2013; 40:

laria. Am

J Trop

Med Hyg

1989;

Turner RC. Severe hypoglycaemia

384-8.

40: 470-6.

and

hyperinsulinaemia in falcipa-

31.

Genton B, al-Yaman F; Alpers

43.

Luse SA, Miller LH. Plasmodium

rum

malaria. N

Engl J

Med 1983;

MF,

Mokela D. Indicators of fatal

falciparum malaria: ultrastructure

309:61-3.

outcome in Pediatric cerebral ma-

of

parasitized erythrocytes in car-

57.

Hall A. Dangers of high dose qui-

laria: a study of 134 comatose

diac vessels. Am

J Trop

Med Hyg

nine and over-hydration in severe

Papua New Guinea children.

Inter-

1971; 20:655-60.

malaria. Lancet

1985; 1:1453.

national J. Epidemiology 1997;

44.

Macpherson GG, Warrell MJ,

58. Okitolonda

W, Delacollette

C,

26: 670-6.

White NJ, Looareesuwan S, War-

Malengrea M, Henquin JC. High

32.

Nwosu SU, Lesi FEA, Mafe AG,

rell DA. Human cerebral malaria:

incidence of hypoglycaemia in

Egri-Okwaji MTC. Hypoglycae-

a

quantitative ultra structural

African patients treated with intra-

mia

in children with cerebral ma-

analysis of parasitized erythrocyte

venous quinine for severe malaria.

laria seen at the Lagos University

sequestration. Am

J Pathol

1985;

BM J 1987; 295: 716-8.

Teaching Hospital: predisposing

119:385-401.

factors. Nig

Med J

2004; 45:9-13.

77

59.

Jones RG, Sue-Ling HM, Kear C,

71.

Stanley CA.Perspective on the

80.

Oyenusi EE,Oduwole AO,

Wiles PG, Quirke P. Severe symp-

genetics and diagnosis of congeni-

Aronson AS, Jonsson BG, Alberts-

tomatic hypoglycaemia due to

tal

hyperinsulinism disorders. J

son-Wikland K, Njokanma OF.

quinine therapy. J

R Soc

Med

Clin Endo Metab 2016; 101: 815-

Hyperglycemia in acutely ill non-

1986; 79: 426-8.

26.

diabetic children in the emergency

60.

Phillips RE, Looareesuwan S,

72. Güven

A, Cebeci

AN, Ellard

rooms of two tertiary hospitals in

White NJ, Chanthavanich P, Karb-

S,

Flanagan SE. Clinical, genetic

Lagos, Nigeria. PediatrEmerg Care

-

In Press (Accepted 23 Septem-

rd

wang J, Supanaranond W, Turner

characteristics, management and

RC,

Warrel DA. Hypoglycaemia

long-term follow up of Turkish

ber

2014 and published ahead of

and

antimalarial drugs: quinidine

patients with congenital hyperinsu-

print).doi: 10.1097/

and

release of insulin. BMJ

1986;

linism. J

Clin Res

PediatrEndocri-

PEC.0000000000000440

292:1319-21.

nol. 2015 Dec 18. doi: 0.4274/

81.

World Health Organization. Man-

61.

Asindi AA. Poisoning. In:

jcrpe.2408. [Epub ahead of print

agement of the child with a serious

Azubuike JC, Nkanginieme KEO

73. Ghosh

A, Banerjee

I, Morris

infection or severe malnutrition.

AA

Recognition, assessment and

.

(editors). Paediatrics and Child

Guidelines at the first referral level

Health in a Tropical Region. Ow-

management of hypoglycaemia in

in

developing countries. Geneva

erri: African Educational Services;

childhood. Arch

Dis Child.

2015

2000.pp.56-60.

1999.pp. 485-9.

Dec 30. piiarchdischild-2015-

82.

Jaja T, Nte AR, Ejilemele AA.

62.

Fang V, Foye WO, Robinson SM,

308337. doi: 10.1136/archdischild

Post-neonatal hypoglycaemia and

Summer M, Robinson T, Howard

-2015-308337. [Epub ahead of

paediatric emergency room admis-

JJ.

Hypoglycaemic activity and

print]

sions: a study in the University of

chemical structure of salicylates.

J

74.

Haymond MW, Pagliara AS. Ke-

Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital.

Pharm Sci 1968; 57: 2111-6.

totic hypoglycaemia. Clin

Endo-

The Nigerian Health J. 2011;11:19

63.

Asindi AA. Accidental childhood

crinol Metab 1983; 12: 447-62.

-22.

poisoning in Calabar. Niger

J Paed

75.

Cornblath M, Schwartz

83.

Idro R, Carter JA, Fegan G,

1984; 11:19-22.

R.Disorders of carbohydrate me-

Neville BGR, Newton CRJC. Risk

tabolism in infancy.3 edn. Boston:

rd

64.

Ernst AA, Jones K, Nick TG, San-

factors for persisting neurological

chez J. Ethanol ingestion and re-

Blackwell Scientific Publications;

and

cognitive impairments follow-

lated hypoglycaemia in a paediat-

1991.pp.1-53

ing

cerebral malaria. Arch

Dis

ric

and adolescent emergency de-

76.

Elusiyan JBE, Adeodu OO, Ade-

Child 2006; 91:142-8.

partment population .

AcadEmerg

juyigbe EA. Evaluating the Valid-

84.

World Health Organization. Man-

Med 1996; 3:46-9.

ity

of A Bed-Side Method of De-

agement of severe malaria: a prac-

tical handbook. 2 edn. Geneva:

nd

65.

Mayefsky JH, Sarnak AP, Postel-

tecting Hypoglycaemia in Chil-

lon

DC, Daniel C. Factitious hypo-

dren. Ped

Emerg Care;

2006; 22:

WHO; 2000.pp.43.

glycaemia. Paediatrics

1982;

488-90.

85.

Koh TH, Aynsley-Green A, Tarbit

69:804-5.

77.

Oyenusi EE, Oduwole AO,

M,

Eyre JA. Neural dysfunction

66.

Gerich JE. Oral hypoglycaemia

Oladipo OO, Njokanma OF, Ese-

during hypoglycaemia. Arch

Dis

agents. N

Engl J

Med 1989;

321:

zobor CI. Reliability of bedside

Child 1988; 63:1353-8.

1231-1245.

blood glucose estimating methods

86.

Menni F, de Lonlay P, Sevin C,

67.

Oyebola DDO. Cow’s Urine Con-

in

detecting hypoglycaemia in the

Touati G, Peigne C, Barbier

coction: Its chemical composi-

children’s emergency room. Niger

V,Nihoul-Fékété C, Saudubray J,

tions, pharmacological actions and

J Paed 2015; 42 (1):39-43

Robertet J. Neurological outcomes

mode of lethality. Afr

J Med

78.

Wilker RE. Hypoglycemia and

of

90 neonates and infants with

1983; 12:57-63.

hyperglycaemia. Cloherty JP,

persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypo-

68.

Bramachari HD, Augusti KI. Hy-

Eichenwald EC, Stark AR

glycaemia. Pediatrics

2001;

poglycaemic agent from onions. J

(editors).Manual of Neonatal

107:476-9.

Care.5 edn.Pliladelphia: Lippin-

th

Pharm. Pharmacology 1961;

13:128.

cott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.pp

69.

Jain RC, Vyas CR. Hypoglycae-

569-579.

mic

action of onions on rabbits.

79.

Elusiyan JBE, Owa JA. Hypergly-

BMJ 1974; 2: 730.

caemia in ill Nigerian Children- A

70.

Jain RC, Vyas CR. Garlic in al-

study of 13 cases. Niger

J Paed

loxan-induced diabetic rabbits.

Am

2006; 33:8-1.

J Clin Nutri 1975; 28:684-5.